Brash broads, ruminating husbands, and the all-important coffee breaks

Eduardo de Filippo’s Grand Magic comes to Stratford

There’s not a lot of theatre from the European Continent at the Stratford Festival usually, so coming across a big ensemble production of a piece by a long-gone Neapolitan playwright in the spiffy new Tom Patterson Theatre is in itself cause for celebration. Antoni Cimolino’s production, in the new translation and adaptation by John Murrell and Donato Santeramo, gives this little known Eduardo de Filippo treasure (‘gem’ is inadequate) an attentive and passionate read. Grand Magic gets a lot of space and time - the play unfolds fairly slowly on the vast three-side jetty of the Patterson theatre stage, with two 20-min intervals.

You could call a lot of de Filippo’s plays sad or tragic comedies and in its march to poignancy through one comedic scene after another, Grand Magic works like that too. But this is an atypical de Filippo play - at least when it comes to what’s mostly performed in translation today, which is Filumena Marturano and Naples Gets Rich (Napoli milionaria!). Historical criticism has described Magic as his most “Pirandellian” work: there are absurdist moments, reality vs illusion distinction wobbles, there’s the messing with the fourth wall, and a number of characters seem to be in search of a stable story. (Story structure that people cling to here is called ‘game’, in the vocab of the illusionist-philosopher protagonist, Otto Marvuglia, and this is well before psychologist Eric Berne became famous with Games People Play in 1964.) Italian Wikipedia tells me Magic wasn’t a success when it premiered in Italy in 1948: in those post-war years, the audience preferred “popular stories, simple and pathetic, like Naples Gets Rich and Filumena Marturano” giving a pass to “this absurdist bourgeois story of a man who believes his wife is in a box”. Having read Filumena, Napoli, and Those Damned Ghosts (all in translation by Maria Tucci), I realize that Magic is much more complex, ambiguous, ambitious, and more likely to still be performed in a hundred years than de Filippo’s more populist fare.

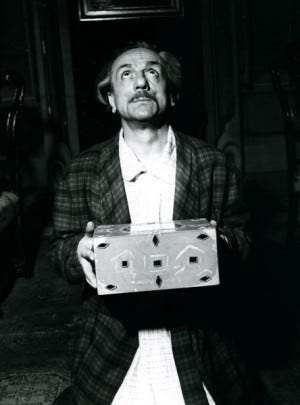

But to rewind to how our man ended up with a box which he’s afraid to open… Act One takes us to a not exactly fancy sea resort where the guests, in between card playing and kibitzing, are about to get ready for the event of the week, the performance by one Otto Marvuglia, Great Magician and Illusionist (Geraint Wyn Davies, his suave baritone voice in top form). Planted volunteers share the stories of horror from his previous “experiments” with human subjects; they are, it will transpire in the second and third act, Otto’s adoptive travelling family. “There is always that one couple which is the main story of the resort”, the gossiping characters agree, and we quickly learn that the couple in question is the possessive husband Calogero di Spelta (Gordon Miller) and his beautiful wife Marta (Beck Lloyd). Rumour has it that he’s so controlling that he sometimes locks her in her room if he has to go out.

The main event of the performance is the disappearing act. By previous arrangement with her and her lover, Otto chooses Marta to volunteer to go into the magic sarcophagus. While Otto and his wife Zaira (Sarah Orenstein, reminiscent of Lesley Manville) distract and entertain, Marta leaves the resort through the back door and elopes with her lover to Venice. Over in the hall, Calogero gets impatient and demands her wife back. Otto summons all his powers of persuasion as he questions his subject’s notions of duty and reality itself: are you sure that I locked your wife? Are you sure she is your wife with her heart and soul? Do you have faith in her? And by the way, here’s a box. If you do not have faith in Marta and her return, you will open it. If you do, you will leave it unopened. Lights go out on Act One with an angry and confused Calogero.

It’s four days later in Act 2 and four years later in Act 3. The second act is the trickiest transition as it’s there that Calogero gets steered from his relative sanity to the world of the ‘game’, the narrative seemingly commanded by Otto but actually wholeheartedly embraced by Calogero himself, in an attempt to make sense of things. He was, almost literally, blindsided by his wife’s departure. From there until the end of the play, Calogero does not part with the box - the way a child would not part with a blanket, or a neurotic ventriloquist with his puppet. Otto has his own reasons for manipulating Calogero: the bourgeois has become an easy dispenser of cash which helps the magician clear out the considerable debts trailing him from his previous social ‘experiments’. There’s a scene with a policeman (something of a comedic trope with de Filippo) in which Emilio Vieira as the laugh-out-loud funny Brigadiere brought to Otto’s house by the irate Calogero almost steals the act from under the protagonists’ noses and takes it home with him. Magic is full of opportunities for character actors, and for the most part in this production, they are well used.

Act 3 sees Calogero in solitary confinement in his apartment – if we discount his long-suffering manservant. Because Otto has convinced him that “time does not exist, it’s an illusion” he has stopped eating and going to the bathroom, and refuses to pay his servant’s salary because “money is fiction”. Calogero’s family visits him for an intervention, his mother, perennially dressed in bereavement black, his sister who married well, his BIL and his younger brother who’s eager to declare him incompetent and take over the management of the family money. Marta, however, also returns – not to come back to him, but to come out clean after all those years, and Otto tries to manage all that stage traffic with his woo-woo talk. The ending is great, is all I will say about it. “What the heart desires, the mind believes” indeed.

Having given myself a crash course in de Filippo before the show, I’ve noticed some themes recurring in his plays. They are present in Grand Magic too.

Coffee! As an important social ritual. It is delicious, and people take time to make it, and being handed a cuppa is a joy, whatever the occasion. There are elaborate coffee scenes in Filumena, Napoli, and Magic. The way people sit down for tea and chat in Sally Wainwright’s TV shows, characters drink coffee in de Filippo’s plays. It’s a respite, drama-wise, the coffee scene, not a place of escalation. You feel they were written for enjoyment - because sitting down for coffee with friends or family means something.

“Strong female characters”. This has become such a cliché, but I don’t think de Filippo could have written a female weakling protagonist if he gave it his darndest. In Filumena, a former prostitute living with her man who won’t marry her because of her past tricks him into marriage, reveals she has been taking his money to secretly support her three adopted sons (who don’t know about her existence) and eventually manages to persuade him to marry her legitimately and love them all as if they were his own sons. One of them is, but which one is the information she’ll take to her grave. In Magic, Otto’s wife gets a marital quarrel scene in which we learn that his wife Zaira’s planning and “scarce resources management” has been keeping his show on the road for years. In Naples Gets Rich, Amelia, the cynical matriarch of the family keeps everyone fed and then some during the war by obtaining and selling rationed food at a profit and growing this into a business from the Fascist era through the American occupation.

Related: women know the ways of the world, and what practically, immediately, needs to be done. The downside correlate: they are proner to cynicism and not exactly pure, under any criterion available.

Related: husbands tend to be dreamers, ponderers, ruminators. In some cases, this leads them to being the only ethical character in the show (Amelia’s husband Gennaro, the unemployed tram conductor in Naples, returning from the war finds his family completely corrupted by the easy flow of money though the household - and jolts them all, in his gentle way, into an awakening, after which their capacity for shame returns). More frequently, this leads them to being a useless bundle of delusion and self-pity. In Questi Fantasmi (Those Damned Ghosts) a husband moves his wife to a fancy new palazzo reputed to be full of ghosts. His wife's lover's brazen appearance in their midst he chalks under ghostly visitations: it’s just something they’ll have to get used to. The money that mysteriously keeps appearing in his PJ pockets he understands to be coming from the generous ghosts as well. The lover i.e. the ghost pays for the couple’s upkeep so his affair with the wife can continue undisturbed.

And what to say of Calogero, the ultimate cornuto-philosopher who believes that akshually he is the one in control.

The less loved are more interesting. If in a couple there’s one who loves more and one who loves less, the one who loves more and is loved less is much more interesting, existentially, dramatically, philosophically, for de Filippo, than the other. That’s Filumena in Filumena, and Calogero in Magic. Otto and Zaira seem to be a rare even-keel couple who have both cheated and still have major rows but love each other madly. (There’s something sexy about this fair distribution - or maybe the chemistry credit should all go to the two actors in this production.)

To sum up: Grand Magic is probably the most interesting show on offer at the Stratford at the moment. An emphatic recommend.

Until September 29th at the Tom Patterson Theatre.

Photos from the 2023 Stratford Festival production of Grand Magic. Top photo: Beck Lloyd (centre) as Marta, Sarah Orenstein (Zaira) and members of the company. Middle photo: Geraint Wyn Davies (Otto) and Gordon S. Miller (Calogero). Photo below: Geraint Wyn Davies with Emilio Vieira (Brigadiere). All photos are by David Hou. The Eduardo pic is from Wikipedia commons.