Can the weirdest Canadian nudes please stand up

Art in the 1960s or how Toronto finally came out of the slumber

How does a city create a lively visual art scene?

Toronto didn’t really have one before the early 1960s, argues the retired lawyer, former Telegram critic and life-long collector Harry Malcolmson in his new book Scene (UTP). Toronto certainly had institutions e.g. the AGO, then called the AGT, professional associations, volunteer-run committees and a deep Anglophilia and devotion to Henry Moore, but no hopping scene to speak of. Then a few lucky things happened at the same time, he reckons. Stock exchange went up, and up and then up some more and there was a lot of extra wealth about. The number of galleries quadrupled and art dealership became a sexy profession. Torontonians with disposable income looked around their living rooms and thought, time to try something new. In the art patron circles, the walls between the WASPs and the Jews came tumbling down.

Plus, the rising nationalism and increased state involvement in cultural investment leading up to the centennial and the Montreal Expo, Malcolmson told me when we met at the AGO cafe tucked behind the Walkers Court earlier today.

Suddenly, and finally (Montreal has had an art scene at least since the end of the war), Toronto arrived. Galleries were packed of a Saturday morning. Around this time, young Harry received a phone call from the Toronto Telegraph arts editor urging him to try his hand at art criticism.

And this he did, alongside a budding legal career, for the good part of the decade. After that, le political deluge: the 1968 protests, the wave of the US draft dodgers, the rise of Quebec separatism and de Gaulle saluting le Quebec libre, the recession of the 1970s. A different scene altogether, which Malcolmson and his wife Ann observed from the sidelines, as photography collectors.

It was surprising to learn of a time when European and British influences were dominant in this city’s cultural life – and that at a delay too – while the Americans were the up–and-comers and experimenters. Malcolmson writes of an art-funding, selling and exhibiting ecosystem that was untouched by the developments in NY’s abstract expressionism, pop art or op art (“perhaps some of Rita Letendre was the closest we had to ab-ex”, he tells me as we walk through the AGO on our way out). Riopelle had moved to Paris already in 1947 and lived as a ‘wild Canadian’ over there.

OK, I say, but does great art have to be global? Can an art scene be regional, local, and still great? I was reading the section on how Toronto rejected Andy Warhol and found myself thinking, good on them? I never really cared about pop art. It was a blip, no?

It’s not so much that, he tells me: it’s that Toronto’s art tastemakers were insular and inward-looking. All the energy was in the innovation south of the border. The Albright-Knox in Buffalo and the AGT/O, while geographically close, were as if from two different planets in the early 1960s.

What turned his attention back to Europe, the book suggests, was Joseph Beuys. But that was later in the decade.

About those nudes

There are portraits in the book of some extraordinary Toronto artists whose rise Malcolmson witnessed, cheered on and helped, or gave a side eye to. (He is not shy about his faves and hates.) Some exhibited abroad, others stayed put. The key galleries, collectors and curators (Jean Boggs and Brydon Smith for example) are highlighted. The scene was lively but not enormous, and it wasn’t hard to know everyone’s business, whose marriage was on the rocks, and who opened a gallery against their parents’ wishes.

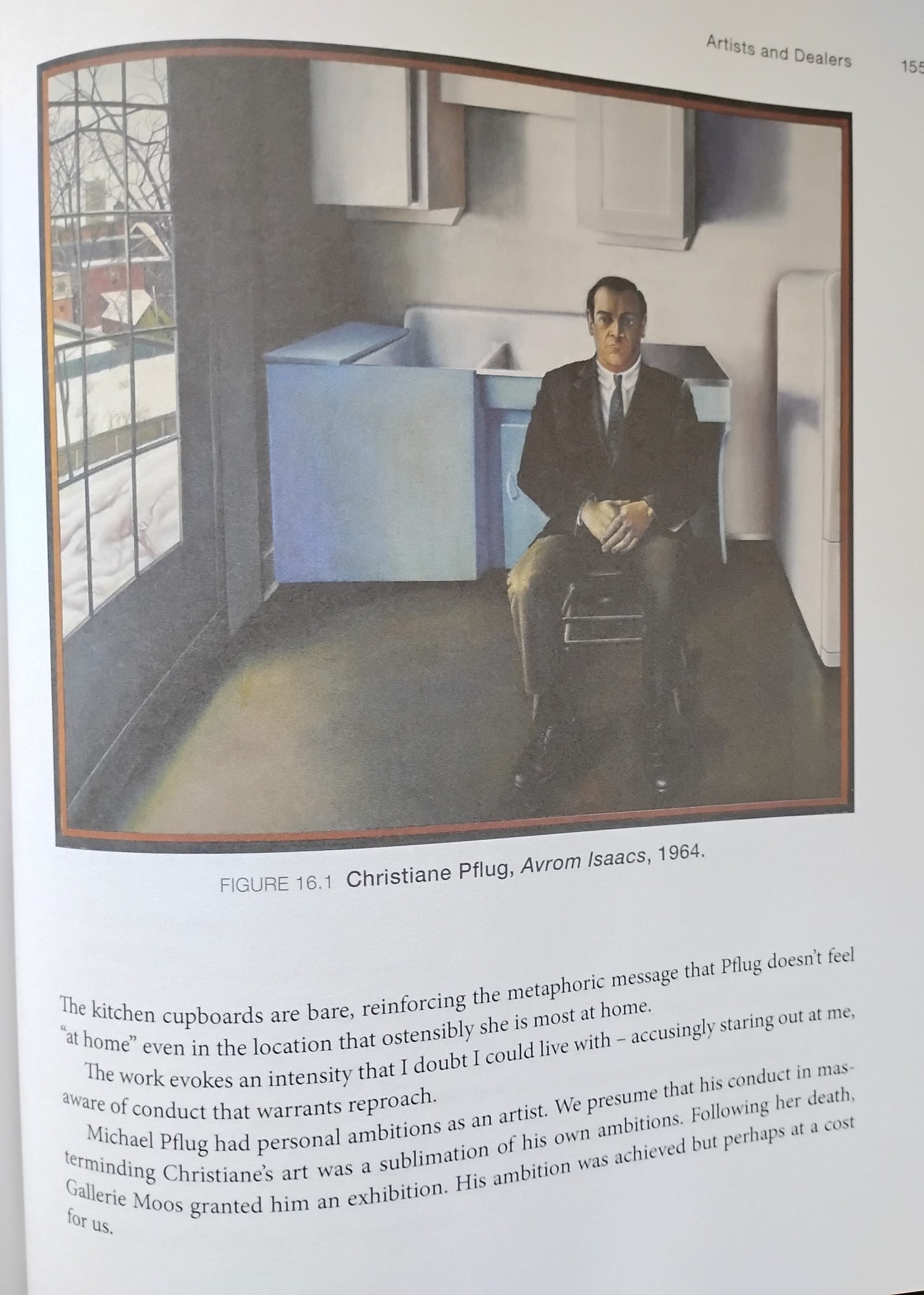

Painter Christiane Pflug, from inside her coercively controlled marriage and her struggle with mental illness, created domestic scenes full of dread. Malcolmson shows us the painting nominally featuring her dealer, Av Isaacs, in which he clearly stands in for someone else, someone much less benevolent.

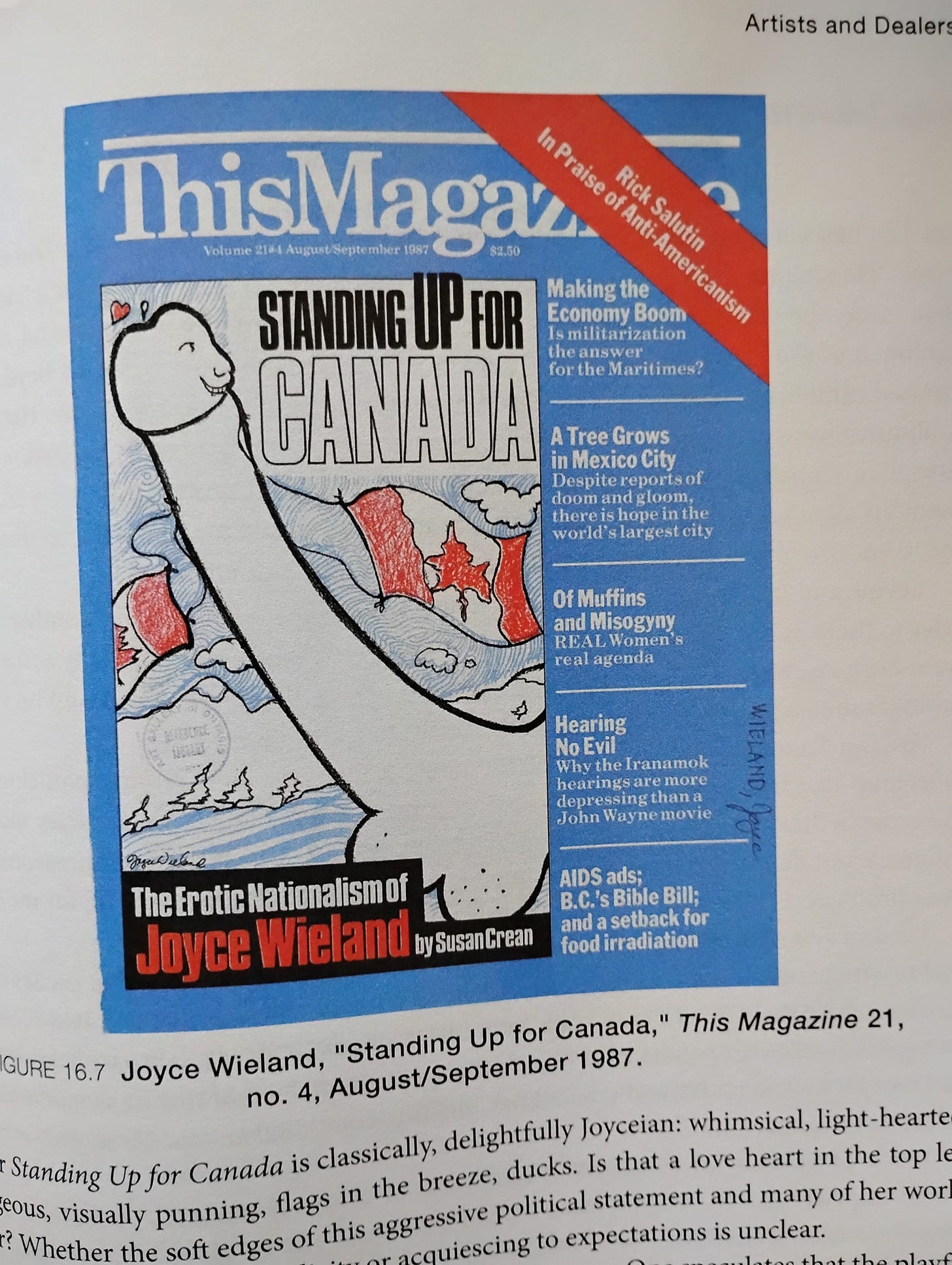

Robert Markle’s splaying, pornography-meets-Otto-Dix nudes shut down a gallery in an obscenity trial in 1965. Gallery’s owner Dorothy Cameron pursued the case to the Supreme Court, lost again, and closed the business for good. When in the early 2000s the AGO highlighted his work alongside Joyce Wieland’s in a revival and re-evaluation exhibit, Sarah Milroy described it as misogynist.

By the way, Joyce Wieland.

Conceptual artists Iain Baxter (“he’s a genius”) and painter Jack Bush remain Malcolmson’s favourites to this day.

English sculptor Anthony Caro, he tells me, was revolutionary. He “upended the long-established tradition of closed form sculpture”. The David Mirvish Gallery brought his work to Toronto.

Back to local talent, you should also know about Dennis Burton (whose abstract geometrical renditions of female genitalia up-close provoked a Diefenbaker denunciation in the House of Commons), Graham Coughtry (again, interesting things with nudes), Paterson Ewen (I’m a big fan on first sight) and Sorel Etrog, whose sculptures you must have encountered.

Which Canadian artists will be known in a hundred years, what is his best guess?

Harry Malcolmson’s Canadian art pantheon, here comes: Michael Snow, Alex Colville, Lawren Harris. Too, Emily Carr, David Milne, and Paul Borduas.