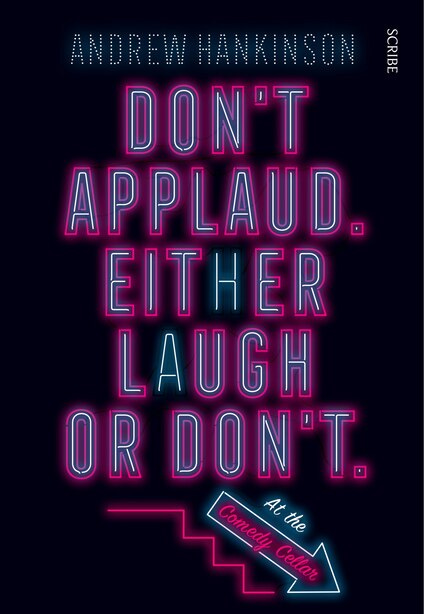

Either laugh or don't

Andrew Hankinson's book on the Comedy Cellar and whether comedy should ever be reined in

*** If you are sensitive today, perhaps skip this one. Content that many will find offensive quoted and analyzed***

When British writer Andrew Hankinson started doing research for Don’t Applaud. Either Laugh or Don’t, he expected the book to be a more or less uncontroversial oral history of NYC’s legendary stand-up club Comedy Cellar. Then in 2017 Louis CK happened. One of the club’s best known regulars and the man who put the Cellar in his then very popular autofiction TV series, Louis CK admitted that the NYT reporting on his history of sexual misconduct was true, apologized to the women who spoke out, and went incommunicado for a year. (For those lucky enough to have forgotten, LCK had a history of compulsive flashing and masturbation in front of women he’d meet in informal professional situations.) After the year of #metoo a lot of other social issues sharpened, US political polarization reached new heights and free speech lost lustre fast under the presidency of a TV star who used his social media platforms to mock, insult, threaten and spread falsehoods.

When Louis CK returned to stand-up after his year of disgrace, it was the venue that let him perform that got all the flak. First time around, a few audience members walked out, though four men stood up to give him a standing ovation. Cellar has a no-heckling, no recording policy, either is an expulsion-worthy offence, so if a disgraced, talented comic is to attempt a comeback, Cellar is quite the ahem safe space for that. But there were hiccups and protests and social media outrage. Ted Alexandro, who in the previous life used to open for Louis, went viral with the new material about Louis’ return.

“But what’s with this PC culture? It’s suffocating right? Do you want to live in a world where a man can’t politely ask a colleague if he can take off all his clothes and masturbate to completion? Is that where we are as a culture?”

And

“He’s lost everything. It’s not fair that a man should lose everything in a flash, and by everything I mean hardly anything, and in a flash I mean a decade later.”

Louis’ own material initially wasn’t very good (staff at the Cellar described it to Hankinson as too angry and avoiding the elephant in the room). But he’d tweak and change, and soon enough the CK audience re-formed itself, was willing to pay for tickets, and Louis was kinda back – if to stand-up only. (One year later, I was buying an online ticket for his one-hour comeback special. It’s not his best work, but it has its moments.) The owner of the Cellar Noam Dworman doesn’t shy away from using the acronym PTSD when talking about that particular chapter. They were getting threats of violence, he says; staff in Cellar t-shirts were getting flak from strangers on the subway. But he never had any qualms about letting Louis perform. One of the recurring responses in the many interviews with Dworman is I’d never tell a comedian what he or she can say. It’s non-negotiable principle for him, and Hankinson more than once probes where this commitment to free speech comes from.

I don’t know how the author originally planned to shape this book, but the CK affair seems to have bombed the structure of the manuscript too. To tell that story, and the story of the fast changing audience sensitivities and taboos, he adopts a going-back-in-time chronology. The book starts with the Dworman surveying the CK comeback fallout, and goes back through various outrages between the audiences and the comedians, inter-comedian warfare, management vs. comedian jostling, and some of the missives by Dworman to various public officials in his career of a small business owner. It ends with a leap to present, with a concluding Dworman interview where he, a Jewish man, defends Mel Gibson’s right to make anti-Semitic movies if he can sell them and if there’s an audience for it. “I’ve always been reluctant to embrace the idea of mob retaliation for something somebody said… I just think it spins out of control and it’s arbitrary. I think the cure is much worse than the disease.” In other interviews he brings up the First Amendment and why it’s so great, and in another conversation, about his garrulous late father who started the business, he mocks Hankinson’s “Gentile question”, reminds him of the verses from “If I were a rich man” and explains that this openness to discussion comes from the Talmudic tradition, the this rabbi says this, that rabbi says that habit of reasoning. (“If I were rich, I'd have the time that I lack to sit in the synagogue and pray / And maybe have a seat by the Eastern wall / And I'd discuss the holy books with the learned men, several hours every day.”)

Dworman is a fascinating, admirable figure: he’s probably one of the few people running anything anywhere these days who is so unreservedly in favour of free speech. Hankinson seems to be less committed on that and many other fronts. Each chapter is a verbatim excerpt from an interview, or a found document. He doesn’t attempt any synthesis or even comment. There is no flow. There is no thesis. Author doesn’t seem to be willing to make a judgment either way in any of the cases discussed. We learn about various outrages by reading about the audience member reaction first, then the back-at-the-Cellar situation – who booked the person, how long have they been performing etc -- and only later what was actually being said, and that without a full context. It’s only in his Acknowledgements, which most readers won’t read, that Hankinson says that he believes all those people are funny and doing their best trying to entertain. But maybe all this is on purpose. Maybe the author is really of two minds and conflicted. I suppose one advantage is that he really lets you make up your mind – while giving you the situation in a series of flashes.

Nevertheless it’s worth persisting, because there’s tons of good stuff here. Various cases are retold when an audience sensitivity button was pushed too hard, and people wrote to the club and campaigned against it on social media. One of those was a comedian who told jokes about a recent news item, the case of a toddler who was eaten by an alligator. (“I wonder what went through his mother’s mind at the funeral… See you later gator?”) A woman in the audience was shocked that anybody could make jokes about a dead child and wrote back to the club, clearly heartbroken. Dworman emailed back to say that as a father of small children he absolutely understands where she is coming from, and that he doesn’t necessarily like everything that’s said in his comedy club. “Sometimes I wince and wait for the next joke”. He offers her a comp for another night, and hopes she’ll give them another chance. The dreary social media coda to this is that the woman complained about it on twitter, the comic RT’d her, and the comic’s tens of thousands mostly anonymous followers piled on.

On another occasion, a comic does a joke about his backpack being searched by the cops. When he objects, the cops say they randomly select people. “Well randomly select Arabs.” The cop says “Sir that’s racist”, and the next line by the comic is “That’s ok, I’m racist.” To that, an audience member heckles and is being escorted out of Cellar. On twitter, she complains. Comic retweets, followers pile on and insult. You’re a fucking slant eyed moron, We’ll be clapping as they haul your ass over the border #DACA, #deport. The woman reacts to abuse (“Ugh I hate white men”), is banned from Twitter.

Another time a comic recalls having sex with his black girlfriend who at some point says to him “I can’t breathe” and the punch line is, Why do you have to get all political during sex.

Other times, there are jokes about the Holocaust (by the Jewish comics). There are jokes about Mexican hotel maids who will reliably clean all the shit left by a couple having sex and, from the same man, jokes about “fucking drunk 18-y-olds”.

As Hankinson lays it out, it’s clear that not all of the offending material is particularly funny, and that some of the offending material is extremely funny. It’s entirely up to the audiences to decide which material passes and which comic doesn’t get loads of bookings in the future. An outlier incident, an errant joke, the odd complaint is different from what Dworman calls “a series of unhappy audiences”. One of the booking managers tells the author that what’s irredeemably offensive varies person to person, and that one year an audience member was offended because a comedian smashed his puppet racoon against the piano keys. (“It’s so cruel!”) But the audience collectively do get to decide what’s funny, and therefore survives, and what’s beyond the pale. There is no better measuring stick, says Dworman.

Lynne Koplitz gets the kudos from her colleagues as probably the only comic who managed to make an elaborate rape joke without getting any complaints from the audience. She used as fodder the recurring pop psychology news items about women getting attached too early in a relationship and men usually wanting to break free – and the “He’s just not that into you” thing -- and she dialled this alleged female trait up for her on-stage persona. If a rapist came in at night, I would kiss him on the lips, was one of the lines. In essence, the woman being raped would get attached immediately upon meeting the dark stranger and freak him out with her neediness. Koplitz extended the joke in further performances to cite her actual address in her bit, and in some venues the security would not allow her to do that. (“What about a few doors down from me? What about I give the address of the law school, here on campus?” No, the answer was still no.) I can’t find the video of this anywhere, which is why I’m just retelling the bit third-hand, which is never very funny, but I understand why there’s no record of it: Koplitz would be torched on social media today if that thing is circulated. (Reddit reveals it can be watched on this Dave Attell Comedy Underground series, which requires subscription.)

Hankinson at one point makes a short break to include an interview with a British comic who comments on the NYC stand-up scene as an anthropologist from another culture. Some of the material that he’s heard sounded openly racist to him, and he was surprised why nobody was heckling. It’s the best behaved audience he’s been in! They are incredibly well behaved. It would be only fair to allow that kind of free speech too, he believes, because some of the stuff he’s heard is not on.

I always thought of British stand up as much sharper and naughtier, but perhaps in this one aspect, ethnicity, it’s kinder and gentler? Or does it tend to avoid (what we now call) punching down? Think Ricky Gerais’ Derek, for instance, as a counterexample – but Derek’s biggest problem is that it’s not funny. But I think that too is an extra-comedic value, avoiding the punching-down direction, and I think it’s relatively new. And mostly a good development in Anglophone comedy. The business of the comic is a wholesale desacralization. Nothing is sacred, if it can make someone laugh. Perhaps the no-punching-down is a moral principle creep?

When I look at the Charlie Hebdo school of cartoons, I have no doubt I’m in front of a comedy culture that has not made punching-down an issue. It’s just not a thing, not a worry. And some of them would probably argue that what punching down is varies person to person. Is punching down making fun of a powerful monotheistic religion? I’d say no, many would say yes, if that religion is minority religion in the west.

I had an interesting exchange with French philosopher Manon Garcia the other week on twitter. (She is about to start teaching at Yale, which I think is relevant.) The NYT did a sympathetic profile of Corinne Rey (Coco) of Charlie Hebdo, who survived the attack on the magazine office, but paid an enormous price for it. It was she who was forced by two armed terrorists to reveal the code to unlock the front door to the building. How does one bounce back from something like that? Lots of therapy, support from friends and family, lots of drawing of monsters and horror. But she is still working today, for La Libé among other places. Prof Garcia shared the link on twitter but also objected that the picture of Coco is not complete. Why didn’t the NYT show some of her recent cartoons which are extremely harmful and nasty to various oppressed groups, she asked. I loved Garcia’s book We Are Not Born Submissive, so decided to wade in and defend both the cartoonist and the profile writer, arguing that any reservations about her output would diminish our solidarity with her. Piece about her cartoons is a different piece, I argued. This one is about this singularly tragic event that happened to her. MG wasn’t entirely convinced, and we left it at that.

Some time passed, and one day MG does share a Coco cartoon, to complain to the Libération about its offensiveness. It took me some time to decipher the funny in this one, alas. Lesbian couples were not allowed access to IVF through national health care system in France then (I think the law to change that is still taking a scenic path through the French Senate), so that was in the news. A loony French royalist slapping President Macron was also in the news at that time; the man yelled the royalist battle-cry, Montjoie St Denis! The cartoon connected the two, warned “are you sure you want IVF, lesbians” (because you may end up getting sperm from a royalist loser)? Anyway: it’s not her best work. So I went back to MG to say, OK I see what you mean. The worst offence however is against comedy. The damn thing, aside its potential or actual offensiveness, is just not funny. (Coco has some better work… for ex on the Pope and on Macron ici.)

So really, comics can get away with anything if the material works. Hankinson in his book describes some cases when the Cellar comics really lost the audiences and stopped sending in the avails to the booking manager. Other comics have the problem of bombing with some audiences and killing with another type only. A female comic recalls her colleague complaining to her that “young women are the worst audience, aren’t they” to which she replied “what are you talking about, that’s who I write for”. There was a time when mother-in-law jokes were cultural currency, when “Polak” jokes were heard on Carson. I wish there are some longitudinal audience studies, because audiences do change. And some path-breaking comedians do create their own audiences and change what the series of audiences find funny.

You’ll notice that I’ve written not a word about Canada. I think there are some dreary years ahead for Canadian comedy. I hope I’m wrong and send counterexamples, please.