Fiction is not a moral beauty contest

Zsuzsi Gartner on writing baroque-n-roll in the age of political sensitivity

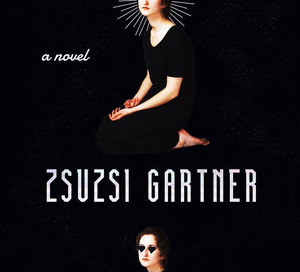

If you haven’t read Zsuzsi Gartner, start with her short story collection Better Living Through Plastic Explosives (2011). That was my gateway drug, and it got me for life. Her first novel The Beguiling (2020) is like one of those busy paintings with myriad figures in the style of Bosch or Bruegel that come in multiple panels. There is one viewer/listener – the narrator Lucy -- but the substance of the book is the multitude of characters who come into her life, tell her about the worst thing they’ve done, and leave the stage. The sentences are chiselled to perfection, there are mythical and fairy tale overtones to ordinary events, and the whole thing is packed with jokes. I talked with Gartner via Zoom about The Beguiling, the publishing world, self-censorship, the cancelling of authors, and much else besides.

LP: This is a very Catholic book, to state the obvious, but in its own unique way… It takes from Catholicism the paraphernalia, the imagery, the pagan elements, the kitsch, all those secondary things that are here actually the main thing.

ZG: That was pretty much me in my youth and adolescence. It was the theatre of Catholicism that intrigued me. I was probably the most Catholic person in my family. My sister is an atheist, my brother atheist, my mother agnostic, my father who passed away when I was young, he was very Catholic. I didn’t have a religious upbringing: it was just me, liking the theatricality of Catholic Church. And then there's the hypocrisy you begin to understand once you move away from it.

Sometimes you’d put something in the Catholic framework, and later on emphatically take it out. In an early story in the book told by a side character, there’s a fetus who is a fully formed personality in the womb. But later in the book, it’s revealed that the narrator has had an abortion, and this event didn’t come with pages and pages of rumination and guilt. It was necessary, and it was done.

I won’t pretend that the book isn’t me and my ideas… It’s like a long form essay disguised as fiction, a lot of it. And I *am* conflicted. Just like Lucy, I’m one hundred AND TEN percent pro choice, and yet there’s a part of me that thinks of it as – if not quite murder in the first degree, then as Lucy puts it, manslaughter. I’m sure people have different gradations on how they view it. Personally I wouldn’t be as blithe about it as the Lithuanian twins later in the book – Lucy sort of pretends to be more blithe about it with them, but she’s really protecting herself, she has complex feelings about it. Whereas when the Lithuanian has an abortion, it was like -- nothing significant happened, moving on. There’s a contrast and difference there.

The fetus with the fully formed personality, which was terrifying and hilarious, murders his twin sister while they’re both in the womb. He’s sort of an evil homunculus.

I never thought of him as evil. In the womb, he’s not thinking This is my sister. It’s more like, here’s this parasite that’s getting in the way of me and my true love. He’s not thinking of it as murder. I have a story in my first book where I do have an actual evil fetus – the story’s called Pest Control for Dummies. The woman finds out that she had a brother who was stillborn and she freaks out – she’s an adult and her mom tells her get over it, if he hadn’t died, you wouldn’t be alive. But she’s OMG my brother died – and she has these dreams that aren’t really dreams, she’s in the womb with her brother, she wants to get to know him… It turns out he is pretty creepy, and she sort of has to kill him in order to survive. That came out in 1999, that story was written in mid-1990s and twenty years later I revisit this. I guess it’s a weird obsession?

The book is also kind of one long series on the mortification of the flesh.

I like that description. An editor that we asked for a second opinion when I finished the manuscript said to us, Oh, all these things that happened, they are all the corruption of love. A lot of the stories start up with the feeling of passion and love and each thing gets corrupted.

Are all bodies freakish? There are no ordinary bodies in the book – and if they’re normal, like Julian, they’re outside the story. And you have all these cases with bodies shape-shifting or losing parts: you have a story within a story of a baby baked in the oven…

Oh, that was one of those scary joke stories going around when I was a kid, that people told at sleepover. It’s a story basically about a stoned babysitter. The parents are going out and it’s Thanksgiving so they asked the baby sitter to put the turkey in the oven at a certain time and temperature. Babysitter gets stoned and the parents get home and look in the crib and it’s the frozen turkey in the crib. And you can guess what’s in the oven. We screamed telling this to each other. I did tell this story to my little brother. Ah the terrible things that we do.

!! Canadian suburban Brothers Grimm! But you have some pretty interesting bodies. People with missing limbs, then dwarfism, then a guy who immolates somebody by accident and later in life starts a meat smoking business…

Can I talk about the dwarf? I hope it worked, I wanted to make it clear that he was really charismatic and she was attracted to him. I spent three months in Ireland on a Frank O’Connor short story fellowship, it was fabulous. I actually lived by the crazy church from the book. I saw more dwarfs in Ireland than at home – maybe I’ve seen two in Vancouver in twenty years. This guy on campus was the man about town. I’d see him in a pub, he’d be surrounded by the people. It really stayed with me – what kind of guy is this, I wondered. What if he’s actually this super political nationalist as well, what would that add to the character. And off I went.

I didn’t consciously think I’d have missing limbs, blindness… I didn’t plan the book like that. It just arose. I guess stepping back and looking at all this – it’s like OKAY… There’s something there. It’s my little cabinet of curiosities.

Motherhood is a huge topic in the book. The narrator is just not interested in having a child. She’s freaked out by pregnancy and breastfeeding, when it finally happens to her – but she’s not opposed to indirect mothering, as we learn later on. She prefers her dog’s company to other people’s.

There are people who like animals better than people, and have never had children and their dogs are their children. It’s pretty common these days. I have a kid, and he’s my best friend. He’s 21 now, lives in Montreal. I dedicate the book to him; he’s an amazing reader and writer. I was really a reluctant mother at first. I was older mom too. To this day I don’t like babies. Being pregnant was OK. But I don’t like babies and the whole first year was a fucking nightmare. And I had post-partum and didn’t realize it. I did become a born-again dog person – I initially got blackmailed to get a dog but love him now. He doesn’t like being touched. He follows us around, he’s conversant, but I wanted a lap dog, and he’s the furthest from it. Now when I find myself on the street and there’s a person with a stroller and a dog, I go to the dog first but have to remind myself, first say What a cute baby. I like most dogs better than babies, that’s for sure.

I read some interviews in which you talk about your son, you seem to have a great rapport.

Oh I’m a fantastic mother. I have so many really good friends who don’t have kids, and actually unless it’s offered I will never ask someone why they don’t have kids. I don’t know if they chose or if they can’t have them. I found it outrageous that people are asked. Or why only one. (They should say Because one’s one too many, ha ha.) I always grit my teeth around Mother’s Day and all that. And based on some mothers that I know… some people should just not have children. Maybe Lucy is one of those. Obviously, Pippa is much better off with Julian who wanted her than with somebody who was so reluctant. It doesn’t mean she can’t love. To mother is different from being a parent. Being a parent is different from giving birth. The whole reluctant mother thing… The idea that so many men leave when their children are young, and nobody goes WOAH what the fuck?! But if a woman does it, OMG stop the presses. Like that’s somehow… twisted. And the guy leaving isn’t twisted. It’s too bad and terrible but it’s culturally acceptable.

Woman’s life is taken over after childbirth, and you have this in the book too. A lot of women go, OK for this period of time – and in some cases for good -- my life won’t be about me and something else will be the top priority. And other women, like the vast majority of men, go: I don’t think I can do that.

Yeah. I compartmentalized for quite a long time. It was kind of: I’m a writer and journalist over here, and I’m a mom, but the mom wasn’t an identity. I know a lot of people who’ve turned that into an identity.

Ahh that’s just it. Some women embrace it as an all-consuming identity.

One hundred percent. I felt I had to struggle not to lose myself. Who I am. It took me a long time to figure it out. I have this side and this side and they can cross but not take over one another. Sometimes I’d say to my husband, John! He’d say, what? I HAVE A CHILD. And we’d laugh.

So yes: we contain multitudes. And also, being a writer is not my all-consuming identity either. With some writers, it is. If they didn’t have that, all of a sudden bottom falls out of the room. I don’t feel like that either.

Maybe this comes from Catholicism too, because it features in so many paintings, but breastfeeding is quite present in the book. And the novel’s very honest about the sort of primordial, pre-verbal eroticism of breastfeeding. Was anybody outraged, did you get letters?

No, nobody said anything. I expected somebody would be outraged about that part with aunt’s breast and her breastfeeding her son until he was five.

I mean, this is bog-standard psychoanalysis – that babies eroticize so they can survive. There’s gotta be something to look forward to, and there’s not much else in a baby’s life.

Yes! Thank you, Doktor Lydia. And then you have the era in which I was growing up. My mother had three kids, she was a Hungarian refugee but she had her kids in Canada, and she never breast-fed any of us. She used formula. That was like the sixties and seventies, it was all about what’s new and convenient.

Your religious readers probably won’t like this desacralization of the image of the Madonna with the child that you have going on in the book.

There's always someone who's not going to like something, someone who will be offended. Few people really tell the truth about motherhood. I think you’ll probably agree, but there’s so many fiction writers that I don’t think are being honest, not just about motherhood but basically always trying to look… morally upright. There’s this sense of gravitas, and the need to say the right thing politically and to be sensitive. And maybe some of them really are. But I think it’s just so much bullshit. That’s why I read a lot of the writers in translation. They just don’t seem so “yes, let’s save the world”.

And it’s not only Canadian. It’s American too. I don’t know if the Britons are there yet, I think their lit and criticism are much ruder and less wimpy…

Wimpy is a good word. There’s so much wimpy fiction.

When you look at our award-giving bodies, I think the awards have always been about all kinds of extra-literary things. Novels are not only or not primarily judged on writing but are seen as representative of this constituency or that social issue.

I had this conversation, about three years ago in Banff. I was at the Banff Centre as part of this Fables for the Twenty-First Century residence. Great program, super enjoyed it. I’ve met so many amazing people, I liked everyone in the program a lot. And at the end we’re out for dinner, those of us who hadn’t left the night before. So there’s about seven of us in an Indian restaurant. It was all very civil, but an ongoing conversation we’ve been having for two weeks. I said, do every one of you feel responsible to a community or communities when you write, or do you write as an individual for individuals. Let me give you the demographic at the table. Two BIPOC guys, straight, two gay white guys who are friends of mine, Jewish lesbian woman who became a very good friend of mine, and another straight woman writer from Newfoundland. Most of them said they feel responsible for at least two different communities – and can I just say, I hate the word community, it’s supposed to cover all kinds of different people as one entity, what, they all know each other? Anyway: I said, I write as an individual for an individual. And the Vancouver writer friend said: There’s no such thing as an individual any more. And they all agreed. This plagues me, this kind of thing. These are creative people whose work I actually respect. And I thought, how can they write good work when they believe this shit.

Are we supposed to be writing now within our own ethnicity? Because that’s the end of fiction.

That would be the end of fiction. But it’s funny who does what these days. Vietnamese-American author Viet Thanh Nguyen has a story with a Black character and a Japanese character, and nobody questions it. And it seems like anybody who’s from anywhere in Asia – let’s say you’re Malaysian, but you can have a South Korean main character because WOW they’re all Asian… Is Asia now one country, one ethnicity? There’s something very wrong with this mindset.

Absolutely. There’s that great essay by Zadie Smith in which she dismantles the concept of cultural appropriation…

I’ve read it – and I’ve read her story about the professor who gets cancelled [which later came out in Grand Union]. It’s a cancel culture short story. She got pilloried for it. “Of all the people, Zadie Smith should know better” etc.

I think here in Canada, especially in the large publishing houses, I’m guessing it would be hard to publish any fiction that’s in any significant way cross-ethnicity.

But if you’re someone who writes social satire or realist novels, or contemporary short stories, it’s not going to reflect reality. I live in Vancouver, and I can’t have a single Native or Asian person in my stories, are you kidding me? It’s ridiculous.

I worry about Canadian fiction. Nobody’s going to want to read the stuff. Most Canadians already prefer to read and watch American things.

I liked your LRC essay on the creeping censorship – from your perspective, coming from places where there has been actual censorship, where there has been repression, and you come here and then you say You people, what are you doing?!

IKR??

It beggars belief. I know emerging writers that are self-censoring like crazy, to the point that they’re paralyzed. One friend who I’ve been mentoring is writing something about some guy swallowed by a whale – she was afraid that it would be misconstrued as stealing some kind of Indigenous myth even though it wasn’t, it was based on the story of Jonah and the whale from the Bible. She phoned me and said Nobody’s gonna publish it, and I thought, well this is silly. And then certain things happened to me with a story. There’s this section of The Beguiling where another woman gives away the baby, the narrator talks with her in the ATM. I did an excerpt from that, it was actually accepted in a major Canadian cultural magazine as a Christmas story three years ago. And at the very end of the editing process, I’m asked to take things out because they will be offensive to people. One was the words “Carl the Harelip”, and that story comes from an old Hungarian superstition – well, “harelip” was offensive. And the other thing was a thought by Arvo Pekka, who you’ll remember from the book. He’s at the Kinko’s in the story, he’s excited to be closing for Christmas holiday and not have to come back to work until day after tomorrow, and he’s saying goodbye to the place, “to Sunita, to the unclaimed and increasingly frightening half-pineapple in the staff fridge which reeked of voodoo, to the bearded guy who’d come in that very afternoon and made a bee-line for Arvo” etc. And the editor told me we can’t have this. We can’t have anything reeking of voodoo because it gives voodoo a negative connotation. Why? Who’s going to be offended?

I write satire and I couldn’t make this up.

I think it’s gotten worse in the last five years, would you say?

Yes. This is all within the last few years. Before that it was not on my radar and I thought it was not going to affect me. And then slowly slowly, it’s affected me.

Then there’s the issue, also rising, that the author has to be morally impeccable in private life to be published.

I will quote somebody who’s not morally impeccable but it’s my favourite quote about writing (I don't care if he was sexist or this or that because he wrote some amazing novels, including one of my faves, American Pastoral), it's by Philip Roth in the Paris Review: Fiction is not a moral beauty contest. I have to put that on a t-shirt. This is what it has become.

You probably followed his official biographer’s cancellation etc. This is what interests me when people demand that works be pulled: Do these people believe they are good and impeccable?

They pretend to be. The people piling on everybody, whenever there’s something said that’s not toeing the party line.

Then there’s the ahistorical revisionism. Nobody’s reading stuff in the context of the world then. Yes some people were nasty, and overtly racist, or anti-Semitic, and when the tide changed they didn’t change. But if that wasn’t manifested in their actual work…

That’s the key.

Take Philip Larkin. Is he a nice guy, a guy you want to cuddle with on a couch? No. He’s nasty. But we shouldn't say, That's it, we're not reading Larkin's poetry anymore because he wrote these terrible things about women and Jewish people in his letters.

Another case in point, Patricia Highsmith. But for me her dodgy opinions don’t take anything away from Edith’s Diary and her best fiction.

I love all the Ripley books and I just got The Price of Salt. I don’t know… I think we can choose not to. I have changed my mind about some contemporary writers – one writer in particular, David Foster Wallace, whose I was a mega-fan of, he influenced my work, and after he died and various things came out about his behaviour and his thoughts and how he behaved towards women… I don’t think of his work the same way because part of his work and his persona was this brutal honesty thing and you bought into that, the presentation of this emotional honesty. But then you find out that there was no brutal honesty, it was a literary performance. It’s still all stylistically brilliant but I’m not going to seek out his work I haven’t already read. There is an essay of his that I regularly re-read, the title is the Latin phrase on the American money, ‘E pluribus unum: Fiction in the Age of Television’. It’s fantastic. Deals with postmodernism… it’s brilliant. I do still love his work, but I feel a little coating of ickiness because I reviewed his biography Every Love Story is a Ghost Story for the Globe and it was a book I wish I hadn’t read. But my mind doesn’t go to Cancel. My mind goes to, We have a choice.