Folk horror’s having a big moment, dare I say a cultural revival. The sophistication of folk horrors that I’ve come across in the last two years has firmly put the genre on my, ordinarily horror-skeptical, radar. Unlike fantasy and super hero genres, which are filling our cineplexes these days, folk horror actually has something interesting to tell us about ourselves.

I’ve been haunted, for example, by You Won’t Be Alone, a North Macedonia-set – but in effect, broader South Slav Balkan – tale of a girl stolen by a witch who in turn runs away from her protectress to explore the world and shape-shifting as she pleases. She becomes a child, then a man, then settles into an adult women’s body, continuing to learn what it means to be a human. She also crosses paths with the old witch once or twice, of course – and we learn that Old Maria’s skin is permanently raw and she a permanently bloodied and hairless monster because she had been burned at the stake as a young woman. (The film, which premiered at Sundance in 2022, was directed by a Macedonian-Australian director Goran Stolevski and can be rented on YT.)

Then about a month ago, a smallish British film Men pops up in cinemas, directed by Alex Garland.

The terroir is the English green and pleasant countryside, where a young woman retreats to work after a ferocious pre-divorce argument inadvertently leads to her husband’s death. The country house owner leaves her the key, says goodbyes, but in the morning she sees a man who looks exactly like him, only in his birth suit, wandering around the house, trying the windows and doors. The policeman that she calls looks like… well, the same guy. (All the men are played by the brilliant Rory Kinnear.) She goes to the village church, meets the priest, who is a long-haired Rory K at his creepiest yet, who tells her, in a fast closing of the male ranks, that she was to blame for her husband’s death because why provoke his fury in the first place. An aggressive boy that curses her because she won’t play has Rory Kinnear’s face. A guy in the pub is a smug Rory K. Many other things happen, but the final scene in the film, and its most horrific one, is a take on the words Man begets man. Her stalker shapeshifts and out of his mouth another man comes out, leaving the old skin behind. Out of this man’s mouth – all this is happening as this creature is chasing her around the country house – comes the next man, the priest, who while pawing her offers a horrified paean to her reproductive capacity (did philosophical and theological traditions declare female sex and everything associated to it as inferior due to philosophers’ and priests’ gestation-envy? in this paper, I will). The final man to come out of the series of men is her dead husband, whom she asks, What do you want from me, tell me? I want you to love me, he says, almost shyly, as his ripped skin is dripping onto the fancy sofa.

The best horror – and that seems these days to be the folk type – reexamines instead of reiterating the terror of the female body and of the reproduction, and the worn out divisions between the pure and the impure, while very comfortably reusing other genre tools. (Jordan Peel’s attempt to do a similar rejigging of the horror genre around the concepts of ‘black’ and ‘white’ ‘race’ was less successful, for a variety of reasons.) The old horror was notoriously hard on women – y’all know about the Final Girl phenomenon – and so are folk tales and fairy tales. But decades after Angela Carter and Fay Weldon, the folk horror films are continuing their legacy in some imaginative new ways.

Canada too had a serious contender in the folk horror revival, and potentially an excellent international export in the CBC series Trickster. If you somehow managed to avoid possibly the most miserable episode in race essentializing among Canadian culturati last year, the show was abruptly cancelled after its co-show runner, Michelle Latimer, was accused of not being Indigenous enough or not Indigenous in the right way. Or something. I couldn’t follow this arcana, and I come from the Balkans, where we specialize in inter-ethnic arcana. The show employed an unprecedented number of Indigenous artists and, aside from all that, actually demonstrated great potential in S1. It didn’t matter, in the end. Its creator was deemed the wrong ethnicity, a lot of her colleagues and funders thought that unacceptable, and the show was kaputt, as was the distribution of her documentary The Inconvenient Indian by the NFB. I love dissing Canadian media as the next guy, but some of the worst coverage of this moral panic came courtesy of the US entertainment media.

The show can still be found on the CBC’s streaming platform, Gem, though you may have to create a profile and register your email to watch it. I binged on Saturday, and while it’s by no means a perfect show, it could have grown up to be the Canadian Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and one more serious about its mythological underpinnings to boot.

It’s small town BC, somewhere on the coastal gas link, where employment opportunities span about two: the fried chicken chain, or drug dealing. (Benefits and stripping are the other two, somewhat reliable, sources of income.) It’s a bleak, always overcast BC and the characters that interest us in this story are almost all Indigenous. We follow a teen, Jared, who is the adult one in his household of two – his mom is a wild thing with a variety of substance issues and voices in her head. He starts seeing things – his own doubled self sitting next to him on a sofa; a skinless, hairless monster going through a trash can across the street; a speaking raven – just as a strange man who’s an old friend of his mother moves to town and claims he’s his actual father.

[Spoilers galore ahead.] And while the figure of the Trickster appears in many cultures, the Native American / First Nations mythology has its own specific take on it. In the Pacific Northwest version, Trickster is related to the Raven spirit, who stole fire from the gods. The Trickster is imagined here as a tradition – and pretty boldly, with its own inheritance, regeneration and transmission rites. The charmer who claims to be Jared’s father turns out to be a trickster… and spectacularly unreliable when it comes to truth telling, which is used to create at least one major curve in the plot.

The man himself seems to be followed around by the zombie-like creatures who are after him because he needs to do something that he, being a trickster, avoids doing: restore the balance of the spheres by returning them to their plane, from which they are exiled. They are the eco-Gaians of the group, it appears, as they are haunted by the sighs of the scarred, overheated Earth in need of relief. As we get to know all the divine and human characters, it turns out that the Trickster is by no means the unequivocal baddie of the bunch. The be-cardiganed Ancients, which are condemned to roam the earth and wear other people’s skins (that metaphor for immigrants is a bit on the nose, hein?) while pining to return to the fullness of home – are not a little irritating in their self-righteousness. And then there are the witches. Jared’s mom Maggie, it transpires in a fab central episode, is a witch – and so is her formidable and very sober mother Sophia, whom we get to meat one third of the series in. Because this is a good show, there are no black and white characters; no one is “likeable”, precisely, and everybody’s dealing with their own shit. Witches are, turns out, not particularly nurturing, and focus on their own business outside the home. They’ll prioritize their own pleasure over your needs. And when Maggie takes Jared’s matters into her own hands, she is a colossally uncooperative PITA.

It’s only trickster blood that can kill another trickster, and while Wade the Trickster pretends that he’s come to town to be finished off by Jared, he is actually planning to do him in so that he can continue for another 500 years messing the order up. (Paging Jordan Peterson: the agent of chaos – and comedy – is a dude here.) It’s all against all to begin with, until the Ancients and the Witches learn that they should pool the resources in the fight against Wade’s plans. Jared as the only other trickster becomes the only person who can stop Wade. Just like in Wagner operas, the hero just starting out is a bit of a moron; genuinely, the least capable person in the room. But he must heed the call.

There is a lot here that overlaps with other world mythologies and stories. It’s no coincidence that early in the show Jared does some homework on Hamlet; he will, a couple of episodes later, be shown unwilling to kill anybody, it’s just no his jam, man. The mother vs. father fight over the loyalty of offspring and over the power to define what’s going on – that’s very much in Mozart/Schikaneder’s The Magic Flute too.

Not all of the dialogue is scintillating. There are some political clunkers which feel inserted into otherwise smooth and logical conversations.

Maggie: “When I first killed Wade… I was so angry.

Sophia: “500 years of colonialism will do that”.

Or

Jared: You always do what you want?

Manic Pixie Indigenous Girl: Pretty much.

Jared: Never feel guilty?

MPIG: No. Guilt is a colonial thing.

But a lot of the dialogue is fresh and totally no-bs – and there’s plenty of it to carry the story well.

Music is smartly used in the series too, and it’s mostly indigenous rap, folk, pop (Buffy St Marie for ex) and in one great scene, a classically trained voice.

And with this series over and cancelled, what else is there available that uses North American indigenous mythologies? I can’t see much, and you would presume that the many activists and bien-pensants would have been busy popularizing these stories in narrative arts. Alas. A few years ago Andre Alexis wrote in the G&M that essentially he doesn’t dare use any of the local indigenous mythologies – of his own country and land – in his fiction because he’s worried about the issues around cultural appropriations, so off he goes, back to the Ancient Greeks and European myth. I suspect a lot of non-indigenous Canadians think this.

It’s no wonder that after 20 years of life in Canada I still had no idea (until I bumped into the info while researching stuff for my new book) that Claude Levi-Strauss spent a huge chunk of his professional life documenting and theorizing – and appreciating -- North American indigenous mythologies. The Way of the Masks is mostly about coastal British Columbia. “The wider system that emerges form his investigation uncovers the association of the masks with Northwest coppers and with hereditary status and wealth, and takes the reader as far north as the Dene of Alaska, as far south as the Yurok of northern California, and as far away in time and space as medieval Europe.” He famously thought that the NW masks were works of art of the same order of greatness as anything found in Ancient Egypt or medieval Europe.

I found this a useful intro to his thought on matters Native American:

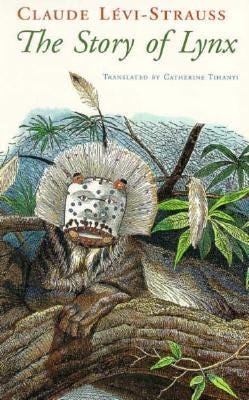

There’s also The Story of Lynx, described as his most general readership-friendly book on Native American mythologies. “In this wide-ranging work, the master of structural anthropology considers the many variations in a story that occurs in both North and South America, but especially among the Salish-speaking peoples of the Northwest Coast. He also shows how centuries of contact with Europeans have altered the tales.”

Meanwhile, we’re still waiting for Canada’s television and movie industry to engage with this wealth.

What we do have, however, is Telefilm’s “commitment to authentic storytelling” ie the procedures in place to secure ethnic and racial eligibility for certain kinds of story-telling. Which was probably prompted by this, but who the fk knows, the ideologues move in mysterious ways.

I’ll leave you with this piece which I’ve been thinking about a lot lately. What does cultural appropriation mean to second-gen migrants – and why are they so sensitive about it, much more than their immigrant parents? https://dailynexus.com/2019-05-31/what-cultural-appropriation-means-to-second-generation-migrants/ TLDR: “cultural appropriation” touchiness as compensation for their feeble and confused belonging to their own ethnic group; a psychic over-investment where there's perceived imperfection and lack.

Talk again soon -

L.P.