Not all of my conversation with Russell Smith made the final version from last week; at one point in our exchange he said Art is amoral, therefore neither immoral nor moral, but outside those parameters entirely. I didn’t go down that road as other topics immediately intervened and took us elsewhere, but two days later I was reminded of his bon mot while listening to this Liberties podcast episode with Celeste Marcus and literary critic Becca Rothfeld. It’s a tremendous conversation. Rothfeld recently wrote a piece on what she calls the Sanctimony Literature: a newly emerging tradition of novels with correct politics which are praised to the skies by the media and popular with readers but are nonetheless failures, she argues, as novels. Two of the most prominent names in this school are Sally Rooney and Ben Lerner for his latest, The Topeka School. (As you can hear later in the conversation, Lerner’s first two novels don’t make the cut and as someone who loved 10:04, I agree.)

You can add all kinds of recent novels here; I’d add most of the novels of the climate change and/or preservation, including Jenny Offill’s Weather, Richard Powers The Echo Maker, Nell Zink’s The Wallcreeper. What’s intriguing about Rothfeld’s argument is that she is not an art-pour-art-ist, but she says that the Sanctimony novels also fail their own inner ethical parameters because, I’m paraphrasing, by failing as novels they fail their own messaging. You need to let the airiness and the democratic spirit into a novel so it would not show its own wheels turning and fail as propaganda too. There are clearly political novels that are great – sometimes propaganda does achieve artistic greatness too -- and there are apolitical novels that end up being used for political goals. It’s complicated. So this got me thinking about some of my favourite novels in English… Margaret Drabble’s probably best novel Needle’s Eye is probably her most socialist as well, and her least political ones, like the Radiant Way, are now being classified in the Hampstead Novel category, gaining a certain bourgeois pedigree. Rachel Cusk’s Trilogy and especially her latest are also gaining an haut bourgeois pedigree and no amount of ‘but she is lampooning the mindset’ will make any difference. (I loved the Outline, but everything after was unnecessary, so I kinda agree.)

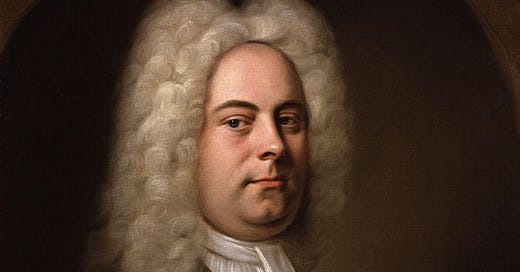

Also last week, the topic of Handel and slave trade resurfaced again in the British media, and with it the recurring topic of the lives of creators and how they funded their art. Handel invested in the Royal African Company, one of Britain’s two official slave trading enterprises, and some of the proceeds ended up funding the Messiah, his opera company, and the Water Music. It appears that Leopold Mozart, who funded his child prodigy, also made some money in the same ‘industry’. While neither the Messiah, nor The Marriage of Figaro, nor (whatever some attempt to argue) Wagner’s Ring advocates for a particular cause too obviously, a lot of people argue today that the unethical funding source or the composer’s political views off the clock dethrone a work or disqualify it from ‘greatness’ in some way. Wherever you stand on that, I appreciate the work of scholars who are unearthing this kind of information. There’s a lot of UK scholarship, for ex, on the ‘imperial countryside’ – mapping and documenting how the many of the grand estates in Britain have benefited from the slave trade or colonial exploitation. Some of you will remember Patricia Rozema’s film version of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park that brings to the fore the undescribed ‘business abroad’ in the novel.

Where I disagree with activism is when it reduces a great work to its (forgive the Christian imagery) worm of corruption. I’m also fascinated by the presumption that we ourselves are, and that the posterity will judge us, and in particular them, the cancellers and the overturners of statues, pure and good. Goodness is extremely rare in any demographic or profession. Are you good? I don’t think I’ve ever met a good person, let alone been one. What are our pension funds doing while we’re sleeping? What is our bank putting our savings into? What of the seven different unrecyclable coffee cups we used last week, 10 minutes each, and tossed away? What of the ice cream we ate yesterday, which requires an industry that keeps cows in captivity, perpetually pregnant? We are stealing another mammal’s milk for our dietary pleasures, how perverse is that? (J.M. Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello: “Let me say this openly: we are surrounded by an enterprise of degradation, cruelty and killing which rivals anything that the Third Reich was capable of, indeed dwarfs it, in that ours is an enterprise without end, self-regenerating, bringing rabbits, rats, poultry, livestock ceaselessly into the world for the purpose of killing them.”) The fossil fuels that our activities require during the day, those that the machines that we travel on burn? I don’t know about you but while I can imagine my life without the car, I can’t without the plane. Old age homes, where we put the frail who cannot contribute to the economy any longer? Who is truly and consistently good to their parents, to their exes, to the customer service staff, to strangers online, no seriously?

It’s delightful to me when large organizations like, say, the University of Toronto advertise that they are committed to decolonization. Sooo they’ll give away most of their real estate and build affordable apartments? Stop taking money from the government and from the wealthy alumni? Remove their pension funds from the financial system and turn them into Animal Crossing turnips?

Who the hell is good? I’ll let them and only them overturn statues and change street names.

There’s a British sitcom from the 1970s, the Good Life, which deals with just this question of living a good life. It follows two couples, one trying to be self-sufficient, grow their own food and live in noble poverty, and their neighbours, proto-Thatcherites and globalists, who have made very different choices. The main good character, the man of the self-sufficient couple, also happens to be a total asshole who’s upended his wife’s life, and turned her into a helper-food producer. Art is conspicuously absent from their lives, and so is the concept of beauty for its own sake.

And sure, argues Iris Murdoch, great art cannot but console what it weeps over by its own constitution, by its greatness. By expanding individual minds, it expands lives. And some great art might lessen them. A lot of great art contains a seed of barbarism. George Steiner wrote about TS Eliot’s crassly anti-Semitic verses, which he analyzed as great verses, when he said that. Two sometimes, not infrequently, come together: greatness and barbarity, beauty and corruption. We should be able to hold both in thought. Two of my absolute favourite operas glamourize evil: Don Giovanni and L’Incoronazione di Poppea. Don Giovanni is especially insidious because while the villain gets punished at the end, the musical body of the opera is on his side; we are this man. The Good in art and the Good in ethics/politics rarely align. But we’re finding it hard to give up this dream -- that all our purposes will magically harmonize.

"Who the hell is good? I’ll let them and only them overturn statues and change street names." Very well put Ms. Perovic! Disturbing behavior supported by some activists, educators and politicians in Canada. Unfortunately, unchecked, it has expanded into the "good" now burning churches..... I will step out on the limb and declare this read to be "beyond good". Should be required reading in fact. Thanks!