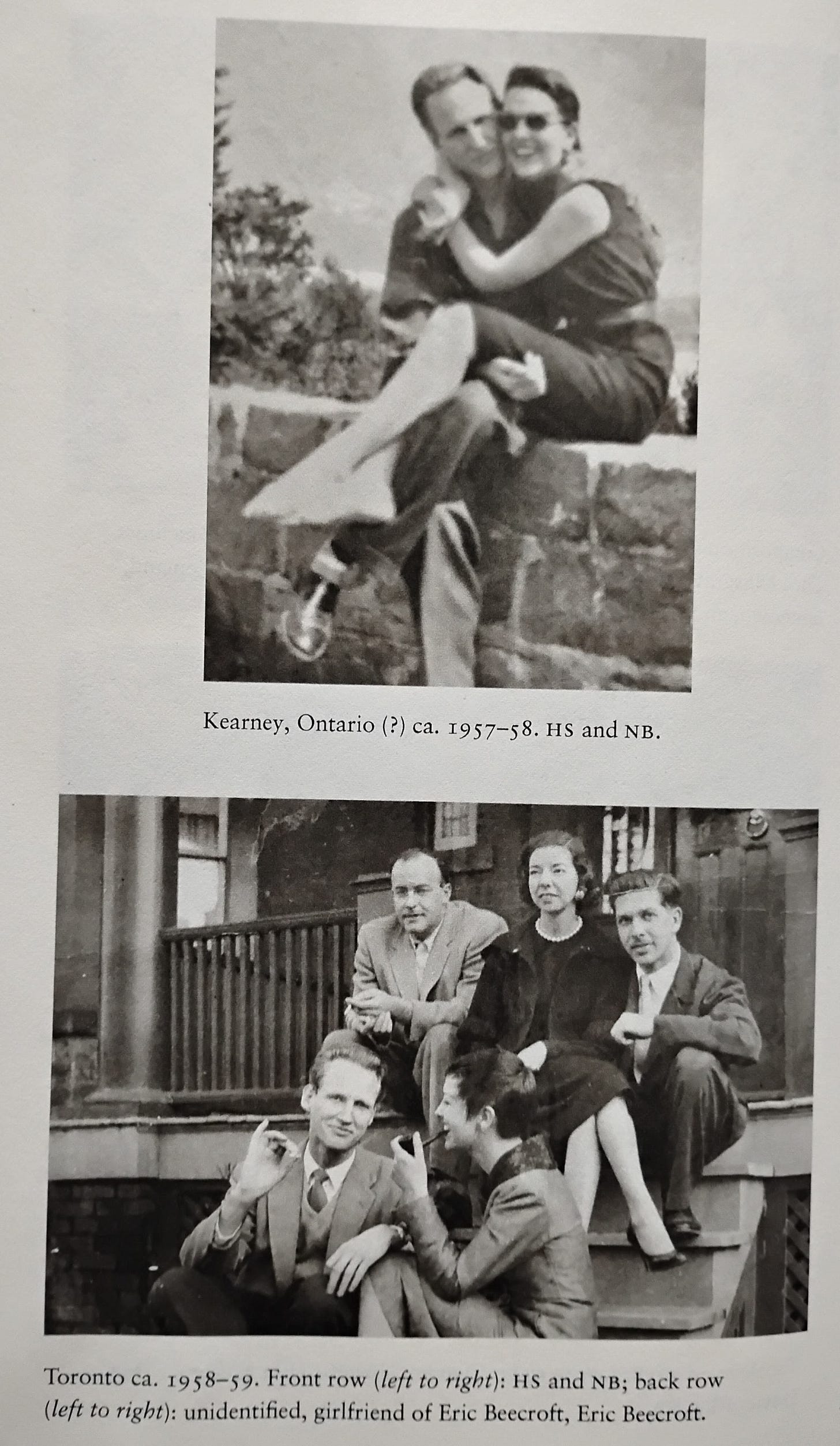

From the mid-1950s into the early years of the 1960, Harry Somers, by then fairly established as a composer, and Norma Beecroft, a young music creator just finding her bearings, had a tumultuous relationship. Mutual friends knew about it — Somers lived separately from his wife during this period - but with the passing of time the affair paled in memory and only reached Brian Cherney in 1975, by the time he was working on a book on Somers, as a vague rumour which he didn’t bother addressing in the manuscript.

The topic reappeared on Cherney’s radar in 2014 and this time he decided to contact Beecroft herself, on the off chance that there would be letters. Somers had died in 1999 and his papers, turned to Library and Archives Canada, contained no letters to Beecroft. Beecroft however still had them all, and lent them to Cherney who decided on the train back from Beecroft that they should be published. Apart from documenting a doomed love, they tell a story of a fledgling new music scene in Toronto, then still Canada’s second city which was about to grow up and fast. Beecroft, Somers and many other musicians appearing in these letters had part-time gigs in the CBC as music copyists, script writers, producers and of course commissioned composers and musicians, and came across each other in the CBC offices. The the role of, again, what used to be the CBC, in the making of these careers was huge.

The letters published in this McGill-Queens University Press collection last year, selected, edited and annotated by Cherney, cover the time when Beecroft moved to Rome to study composition. This will turn out to be the final phase of their relationship. While they lived in the same city, it was Somers who wouldn’t commit to something permanent, but as soon as Beecroft went away, she became more appealing, and Somers suddenly wanted—while still doing nothing much about his marriage in the doldrums—serious commitment from Beecroft. “The more deeply involved I become in music,” she wrote from Italy, “the less I wish for domestic life.” Beecroft joined the class of Goffredo Petrassi at the Santa Cecilia Academy and entire worlds opened up to her.

Five months into this long-distance relationship, Somers blew it all up by showing up in Rome and causing a massive row. After the ripples settled, the two went their separate ways, Somers back to his wife (!) and Beecroft towards a career of a composer and electronic music advocate. But it was not a happy ending for either, at least not immediately. Some years later, Somers’ wife Cathy Mackie, after he embarked on another intense affair, took her own life. (The actress Barbara Chilcott was to be his second and final partner.) Beecroft married, but divorced within a couple of years due to the other party’s alcohol problem. The subsequent partner was her life-long relationship.

The two composers moved in overlapping circles, but a key figure as for many others was John Weinzweig. Somers had studied with Weinzweig in the 1940s and continued to consult him over the years on matters professional. He considered John and his wife Helen close friends. Beecroft had visited the Weinzweigs in their North Toronto home on a weekly basis for theory lessons and considered John and Helen a second family. We now know a little bit about the Weinzweigs marriage too, thanks to Helen Weinzweig’s late blooming career as a novelist. Long-standing readers of this newsletter will know that HW is one of my favourite 20th-C writers, Canadian or otherwise. A couple of years ago, in the dregs of the pandemic, I spent some time with her papers at the Thomas Fisher Rare Brooks library at the U of T, where I’m way overdue for another visit. Here’s how it went down:

“I” is easily used these days

If you haven’t read Helen Weinzweig (1915-2010), you’re missing out on one of the best Canadian novels of the twentieth century – one of the best novels period. I am talking about Basic Black with Pearls (1980), her second and final. It came out when she was in her 60s, garnered accolades at home and in the US, earned her the Toron…

In short, after a life dedicated to “The Care and Feeding of a Canadian Composer” (paraphrasing here one of the first pieces that she published in which she gently mocks her husband in the Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner vein) Helen took a lover—fodder for her novel Basic Back with Pearls—and decided to do something about her life-long desire to write. As luck would have it, her work, though much smaller in volume, is now better known than her husband’s among Canadian consumers of culchah. Weinzweig’s music is little performed these days (Judy Loman, for whom he wrote Concerto for Harp and Chamber Orchestra in 1967, describes it today as “perhaps a little dry”). Either the concert programmers have lost the ear for serialism, or, while being a tremendously important pedagogue, Weinzweig did write dry and joyless music? If anyone know what I should give a go to, send an email.

This was a heady, incubator, R&D era for art music in this country, and some aspects of it are well documented, I’m glad to report. If you’d like to look at it from an angle of one of the first Canadian opera singers who had an international career, you could do much worse than to read Maureen Forrester’s lively and information packed 1986 memoir, Out of Character (with Marci McDonald).

Forrester wasn’t a modernist by affinity, but a truckload of new music was commissioned and written for her voice specifically. As for her marriage with Eugene Kash, it fell apart in 1974, after 5 children.

Claude Vivier is not far behind this generation, but he will leave for Europe and live a life on both sides of the Atlantic. Bob Gilmour’s book is the most informative vita around and when a journalist—why, me—asked him about Vivier’s relation to the modernist avant-garde, he described it as incorporation-and-overcoming rather than a rebellion against. His love life was… well, where to begin.

Fascinating. Thanks. What a lively scene and wonderfully cross-pollinated with the playwrights of the day, Mavor Moore writing the libretto for Somers' Riel and Somers' writing the score for James Reaney's Night Blooming Cereus and other works. We have such a rich cultural history and treat it so shabbily. I love, too, how you note the importance of what used to be the CBC.