My working life: Will Firth, translator

English speakers read very little in translation. Meet one of the cultural heroes of our era: translator from a small language

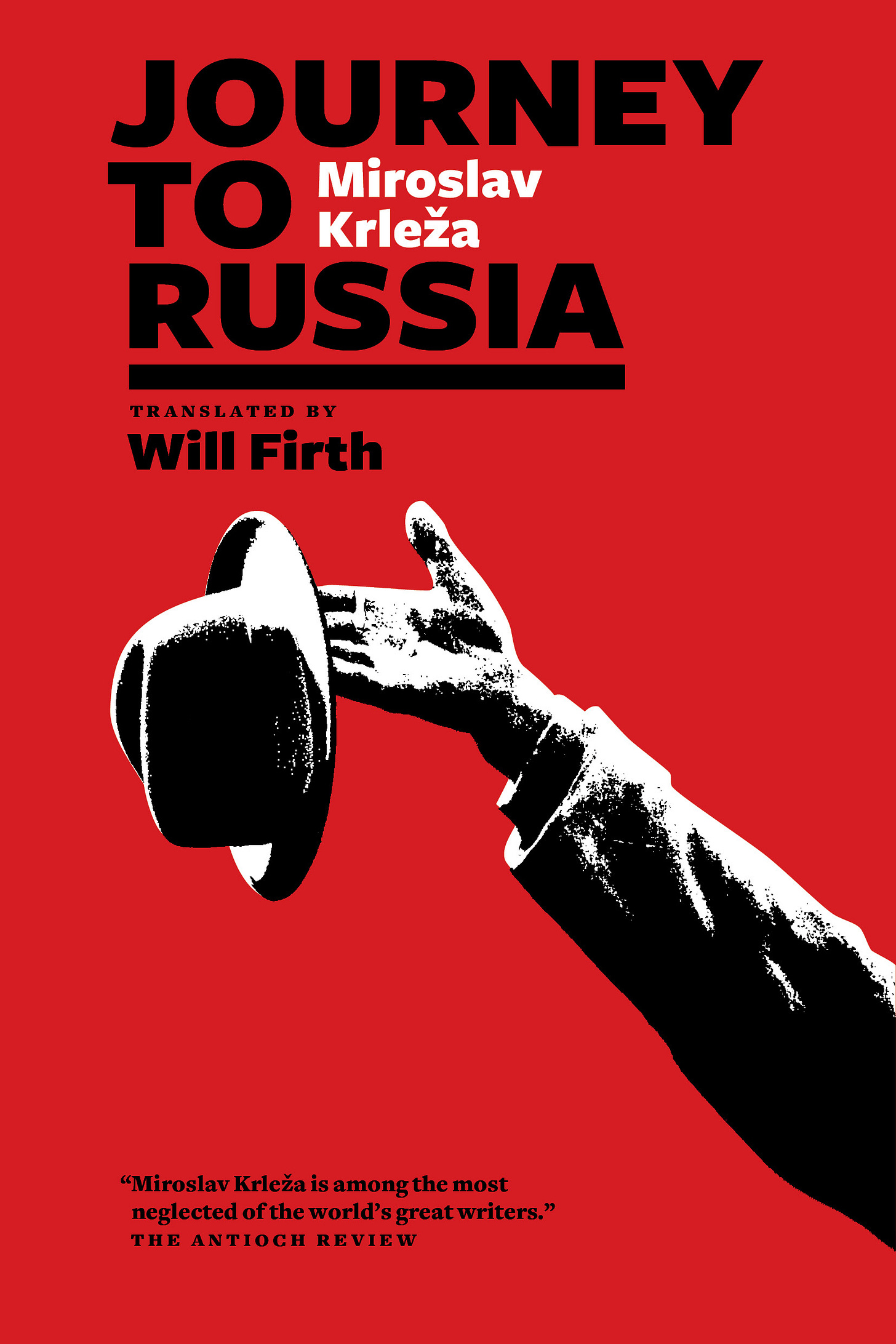

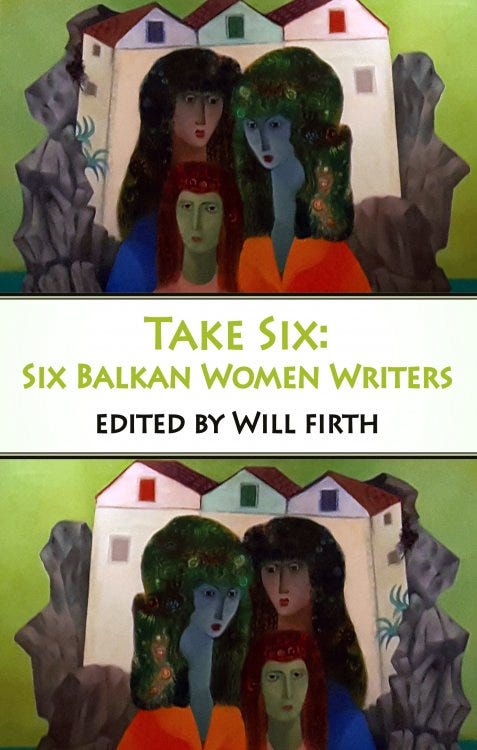

If you’ve read anything translated from the South Slav languages in the last twenty years, chances are that Will Firth was involved. He is one of the remaining handful of translators and commissioning editors advocating for fiction from the language now complicatedly known as Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS). Firth, an Australian who lives in Berlin, also translates from Russian, Macedonian and Esperanto into his two target languages, English and German.

WF: It all started off with me studying Russian and German at the Australian National University in the 1980s. And I realized part of the way into my degree that I didn't really have a plan for what I'd be doing after the degree. I imagined that if I used Russian as a springboard to learn Serbo-Croatian or BCMS and Macedonian, which were and still are widely spoken community languages in Australia, that I might be able to work as an interpreter in the health service and for the courts. So my prime motivation was practical. I'm a philologist essentially. I quickly learned to love the grammar and the semantics and the dialects. But I'd never really been a bookworm and literature is something I got into quite a bit later. The prime fascination for me is with the languages.

LP: How frequently do you find yourself in Southeast Europe?

Once or twice a year. My home away from home is Zagreb. I also frequently visit other parts of Croatia, and Montenegro and Macedonia. I haven't been to Bosnia much and there's not much that takes me to Serbia.

Do you read book criticism at all? I take it it still exists in Germany and people there read book reviews?

I should read more criticism. I probably read a lot of the reviews of books in the Southeast European language, though not a lot are being published in English. More get published in Germany. I haven't studied this in detail, but when I see how much gets translated from BCMS into Polish, for example, or Bulgarian, or other languages in the region, the Germans and the Austrians aren't all that good. But certainly better than the Anglosphere. Just in terms of coverage of contemporary literary trends and so on. In this context, I should mention the network Traduki, which you might have heard of. It's a funding network made up of, I don't know, about 25 or 30 government bodies and quangos from a lot of Central European countries and Southeast European countries. And the main objective of this network is to fund events and fund translations between German and the Southeast European languages, the Southeast European languages and German, and among the Southeast European languages themselves. So they’ll fund something like 10-15 translations a year, organize conferences, invite readers to the book fairs in Vienna and Leipzig. That's a very influential and very important network for the furthering of literary communication between Central and Southeast European countries.

What is the political economy of the working life of a freelance translator from small languages?

I'm very glad you're asking that question, because not many people do, but it's such a vital piece of how I make a living. I do make a very modest living from literary translation. It's not easy. Earnings are not good. In fact, per page or per thousand words, I earn almost as much as anyone else I know, but it's still not enough to make a good living from it. Somewhere near the minimum wage, I guess, is what I end up earning for 50 to 60 hours of work a week. On the other hand, it's a very enjoyable profession. I'm glad to be a literary translator. I wouldn't like to do anything else. It's a kind of privilege, I guess, to be in this very cerebral, high-pressure, attractive niche. I like it, despite the drawbacks.

And please keep at it. There are not a lot of you left. There are maybe a handful of you who translate from the languages of the Western Balkans into English.

There are only a handful of us who are doing it regularly, full-time or part-time, and getting a lot of the contracts, but I think the spread is significant. There are lots of emerging translators and people who are really just doing it on the side, in their holidays, on the weekend, out of passion. And if we count them as well, I think, from BCMS into English, it might be two dozen, three dozen. We'd need to do a brainstorm, look at the books that have come out in the last five years, and I think we'd find that the spread is considerable. But there is a little band of us who are doing more than the others, if you like.

Do you see any significant difference in trends between the Angloworld and, say, European literatures and publishing? We have the publishing consolidation in the English speaking countries, and the agents, and the MFAs - something that literatures on the Continent largely do not have.

Hmm. I guess I can't really see the wood for the trees. I'm very much focused on trees: my authors, my projects. I don't go to the big book fairs like Frankfurt and London very often. That's where the rights tend to get dealt with. I'm a fan of the Leipzig book fair, which is a bit smaller, and everyone says it's a little bit more intimate. There are lots more readings, and translators get to talk to the authors, and the authors intermingle more with the audience and the readers.

Do you notice any broad aesthetic differences between the novels you read in foreign languages versus the novels in English?

One way of approaching that and of answering your question might be to look at the issue of foreignizing or domesticating complex foreign literature when translating it into English. Like, are we going to simplify it so it's going to be digestible for what we might perceive as the average educated reader? Or are we going to leave it wild and complex and incomprehensible, not have any footnotes, just let readers make of it what they will. That's an issue that's discussed quite frequently, and I'm a bit of a fence-sitter on that. I can go both ways and tend to make my decision contingent on what the publisher wants. Some publishers are a bit bolder, others are a bit more reticent, aiming for a middle market somewhere.

But what's your perception of those big trends? You also read Southeast European literature. What would you say?

Oh, I think there's a growing gap between English-speaking world and the rest of the world, probably due to those factors that I mentioned. When I read anything in translation, it strikes me as coming from another planet. And also criticism here is changing. (It’s almost completely gone in Canada; not even the Giller shortlisted novels are being reviewed any more.) There’s also the domination of the me-focused writing. Meanwhile, fewer and fewer people read literary fiction. I'm sure you caught some of the articles in the last few weeks, one documenting that even people who go to the Ivy League schools to study literature have problems finishing a book.

Yeah, my gut feeling is that the trend is similar here, but that maybe there is a slightly larger slice of the population that reads books regularly. Although in Germany, for example, there isn't such a culture of book clubs like you have in the English-speaking world, where people get together one evening a month and discuss a book that they've all read. But maybe there is a bit more of a living tradition of literary criticism. In fact, I have an interesting anecdote. This is about 10 years old, but I think it's still valid today. I did an interview with the Macedonian writer Rumena Bužarovska, and she complained that there was no living tradition of literary criticism in Macedonia today. And I think she's probably right, and so I translated this for a German literary website, and I got a very negative response from the editor who said, how can there not be living literary criticism? That's not possible. She must be making this up. She must be bitter or must be pursuing some private agenda.

Smaller cultures do have this problem.

The reviews, the few that come out, are usually blurb-ish. They're either from someone closely related to the publishing house or a friend of the author. I forgot the English term, but it's like when you do someone a favour by writing them a review. A friend will write a review for a friend or for a colleague or a relative. And there’s not very much objective, founded, popular or scholarly, whatever, you know, real objective criticism. And yes, the smaller countries are deeper in this conundrum than others, I think.

I don’t think Montenegro has reached that stage either, to have a Mandarin class of art critics gainfully employed in the media. But now the Angloworld seems to be reverting to the pre-criticism age! We’ve had maybe 50, 60, or 100 years when literary criticism existed and now… with print culture gone, it’s on its way out too. Apparently nothing sells books like BookTook influencers. There are BookTook tables in bookstore chains now. “As recommended on BookTok”.

What sort of literature is it? Is it sometimes quality literature?

Well, that's the big question. It’s often genre fiction. And you can also see – or am I being paranoid? - in some of the popular literary novels today that they come out of and address a fandom culture, or that they have been sort of pre-written by the anticipated reception on the social media.

I can imagine that's going to follow here as well, but I haven't heard of it being a big factor in Germany.

I don't know if you've read Tim Parks - he often writes about how literature in English is changing too because foreign rights are now sold globally before publication. The novels don’t have to prove themselves to a national audience before being sold abroad, so they are being written in a globalized language, with globalized themes. Have you noticed this at all?

I've heard other people describe the situation in a similar way. My gut feeling would be that this is something that affects the crème de la crème, the most successful prospective writers.

But, as you say, the fact that writers might be aiming for this path, aiming for this kind of audience and trimming and tuning their language accordingly, I'm sure that's an issue. I myself am sometimes in the position of aiming for a kind of mid-Atlantic English that's going to be palatable to both British and North American readers. And there was even a Macedonian novel where I was a co-translator and I aimed for a mid-Atlantic and mid-Indian ocean English that was going to be intelligible to Australian readers and U.S. readers. It was a juggling act, and we did it intentionally. And this was for a small print run, not a large corporation.

Apparently, British novels are being tweaked for American editions as well.

I am currently dealing with a publisher in Perth, Western Australia who would like to publish a German novel and although I don't normally translate from German into English if funding gets approved I will translate this novel next year. And I said to the publisher, I'm really looking forward to this project, I hope it comes through, it will be only one of the two books that I've been able to translate into Australian English and she said, Will, don't get your hopes up. The Americans have colonized us psychologically already. Even if I were just going to market the book to Australians, it would have to be something that was halfway to American English. And for that I'm going to look for a US and a British partner to help publish it globally. It will have to be essentially in US English and any Australianisms will have to be ones that Americans will know.

It’s probably too late for any of us. We’ll all write in ersatz American.

And I mean, there’s nothing wrong with American English if it’s native speaker American and not internet English, Euro English, or, don’t know, Indian English, for example. This mélange that you have on the internet where vocabulary gets really, really cut down to the bare basics, and being comprehensible to the whole world is the main priority… this really reduces your freedom as an author and a translator, to articulate things. It should be permissible to write in a dialect or sociolect, to bring that out. Let’s hope those freedoms don’t get steamrolled by the globalization of English.

How do you choose translations - or do they choose you? Does a publisher ask you? Or do you usually read something, like it, and then pitch it?

A bit of both. I'm always glad when a publisher approaches me. But that doesn't happen enough. Usually it's an issue of me discovering a book or someone recommending a book to me, me reading it and thinking, yes, this would be good to translate. Where is there a publisher? Where is there funding? Almost every translation project that I do involves a fair bit of canvassing, a fair bit of searching, helping with an application or two for the funding.

Did you ever look at the text and you liked it as a reader but you thought this is just not going to be translatable?

Yes, yes, but what's not translatable? At the risk of dumbing things down or making them too bland and too Mid-Atlantic and Mid-Indian Ocean. That's what this co-translator and I wondered regarding the Macedonian novel. It was written in the dialect of the mountains around Bitola, southwestern Macedonia. Very exotic, rather antiquated language as well, so it was sort of a dialect and almost a century old. And we tweaked and pruned and edited and discussed things endlessly until we had battered the language into a pleasant, enjoyable, nuanced, but more standard English. We had to shed a lot of the dialect features. And that's a book where I think a lot of people would say, you can't translate that. That just won't come through in English. And maybe a lot of stuff didn't.

I think if you're going to do full poetic justice to southwestern Macedonian language from the early 20th century, who's going to be able to read it? We could choose, we could either make up a dialect in English ourselves, or we could choose some obscure hillbilly dialect, or I don't know, Scottish, Orkney Island-ish? These are all legitimate strategies, but if you're aiming to have a book that's going to be read by at least a few thousand people, it will need to conform to a more standard form of the English language.

I'm sure there are translators who would disagree with this, but that's the strategy that I tend to go by, that comprehensibility is the main thing, the thing that's most important.

What do you like reading these days? For pleasure?

I have very broad interests. I'm interested in political theory as well, and environmentalism, and history of the trade unions and the left. So actually reading fine literature in my free time, which is very limited because I work such long hours, it's not something I do a lot of, to be perfectly honest. What I do enjoy reading are writers I've discovered through the years. I love short stories, so I love reading stories by Isaak Babel, the Soviet short story writer. He's long dead, but I like German writer Heinrich Böll.

There are lots of little literary circles in Berlin where I live, and once or twice a year my wife and I will go along to one of the readings of these young local prose writers and poets, and that's very fresh contemporary stuff that doesn't always end up being published. I guess that might actually be my most frequent, most direct tap into contemporary literature, if you like. It's like flash fiction, short stories and stuff, that they'll get up on stage and read.

And, of course, I read a hell of a lot of Southeast European literature. Rumena Bužarovska, for instance. She is a shooting star of the Macedonian literary scene. She has a full-time job as a professor of American literature at the University in Skopje. Otherwise, she basically writes short stories and brings out a collection every three or four years. Her language is very playful, very witty, often a bit dark and grim. Her best known collection is probably My Husband, in which nine women describe their husbands. And as you can imagine, the descriptions are rarely very complimentary to the men. It's a kind of a small psycho portrait of Macedonian men today.

I like reading pieces by Boris Dežulović, the Croatian-Bosnian satirist and columnist. I read a lot of what my writer, Andrej Nikolaidis, writes in the Montenegrin press. His polemics are often rather strident and one-sided, you could perhaps say, but so brilliantly cynical and lucid at the same time.

I pick and choose all over the place.