And lo, there’s another project about “the Whiteness” coming your way: U of T Art Museum’s Conceptions of White (Jan 11-Mar 25). It’s a collection of objects and installations that purports to illustrate the many ways in which “the white race” is an invention (accurate) while also capitalizing the word “White” throughout its written materials and taking the concept extremely seriously. “White” is a tenuous concept – and also “White” is all-powerful and always on the march. Perhaps it’s possible to present an exhibition that believes both at the same time, but this U of T exhibit just comes across as a random and highly US-centric collection of loosely related stuff, accompanied by some atrociously written didactic panels. (I always try not to hold the panels against the work itself, otherwise I’d have to give up on visual arts altogether.)

There are definitely a few good ideas here. The various points in modern history of art and the classics at which a number of influential historians and thinkers decided to put a straight line between Classical culture and certain Northern European nation states – that’s a bottomless treasure chest of issues to tackle. But the plaster replica of Apollo Belvedere (c. 120-140 AD) displayed here, and a long accompanying explanation that it was Winkelman, so captured by the Roman copy of the Greek bronze original, to blame for the whitification of the classical sculpture does not do the topic justice. The place of classics and ancient Greek philosophy in formerly imperial national cultures like Great Britain, France and Germany has been examined and reexamined practically for centuries now, and the classics as an academic discipline have been in serious turmoil for years (interestingly, it’s the left and liberal progressives in the academe of the angloworld who see the classics as irredeemably “White” these days). Classics have been off the race wagon for quite some time however; it would fairly peculiar for anyone to state that the 5th century BC Athenian males who formed the city-state’s citizen assembly, for example, were in any contemporary sense of the word “white” (this quarrel on that very topic between Edith Hall and the British Museum curator of “Beauty in Ancient Greece” Ian Jenkins is worth listening to; starts at 25:12). The Ancients are still present in European cultures for a variety of reasons, but the Greek beauty ideals not so much. Aphrodite and Apollo stand no chance before Instagram, Hollywood, the fashion industry, OnlyFans or PornHub.

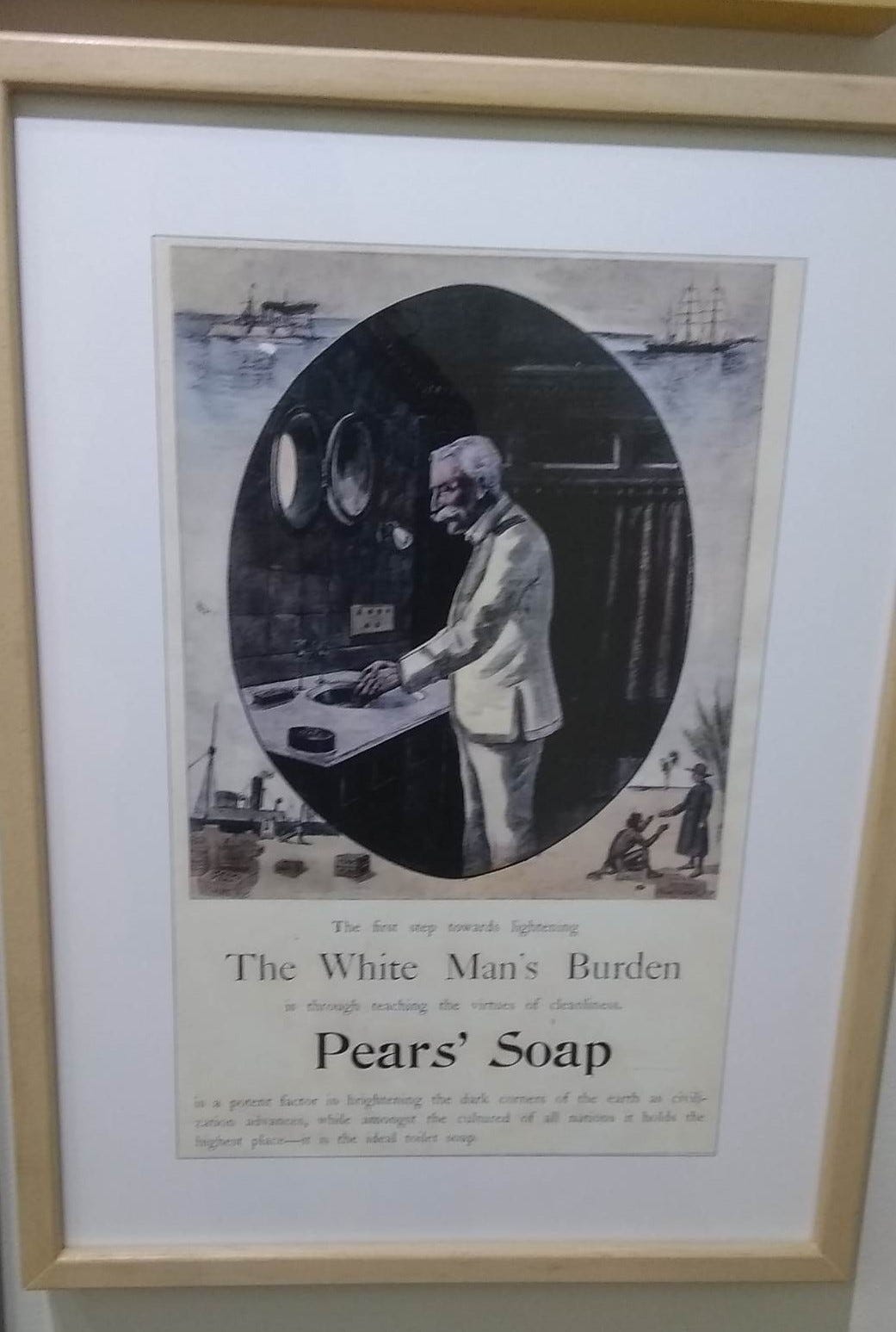

Another section worth spending time with is Deanna Bowen’s “White Man’s Burden”, a wall-ful of reproduced photography, photo negatives, paintings, scans, microfiche, clippings that show instances of racial othering and ideological uses of science. Some documents are left as they are (for ex the scan of Tommy Douglas’ MA thesis cover from the 1920s, The Problems of the Subnormal Families) while others have been flipped upside down or turned into negatives. Unlike a lot of what’s on offer in the exhibition, this part has considerable Canadian content but not a lot of context. (Tommy Douglas for ex abandoned eugenics by the time he became premier. And is the ‘gene-editing’ for Alzheimer genes, for example, a practice already on the horizon of medical science, a new form of eugenics, or something entirely different?) Still the wall is interesting to look at; some of the ads and reportage that appeared in serious magazines are blunt reminders of a not so distant past. Bowen’s contribution acknowledges, in a round-about way, that “white” and “black” have emerged together and that if “white” goes (and I would happily live in a world where the concept of “white race” is retired) so must “the black”, a step which the latest generation of anti-racist activists are not willing to take and would be adamantly against. Yet we have retired “yellow” and “red”, thankfully, but “black” and “white” keep on keepin’ on.

It’s of course partly because they’re hugely important categories in US politics and culture, and we are all American now when we talk about ‘race’. So it’s no surprise that a good number of works exhibited here are narrowly American, which is presented as globally relevant. Ken Gonzales-Day’s “The Wonder Gaze”, St. James Park (20006-2022) – wall-size magnified photography of a lynching with the victim’s body digitally erased – is a powerful and moving statement. The “lynching postcards” were only produced and sold in the US, however. The two videos are even more American, Howardena Pindell’s Free, White and 21 (1980) and Arthur Jafa’s The White Album (2018). But there is no sign of, say, James Baldwin in this exhibition, who knew that “white” and “black” rise and wane together in the US. He was also, effectively, a precursor of the psychoanalysis of race through his essays. (“White people...have quite enough to do in learning how to accept and love themselves and each other, and when they have achieved this — which will not be tomorrow and may very well be never — the Negro problem will no longer exist, for it will no longer be needed.”) But Baldwin’s political offspring is more difficult to subsume under this black and white framework: Zadie Smith, Tomiwa Owolade, Thomas Chatterton Wiliams, Kmele Foster, John McWhorter and that entire cohort - and in Canada, Scott Fraser for ex. And what of ethnicity and ‘race’ in fiction and art today? What of the Pretendians and the Rachel Dolezals? The “whiteness” exhibit is firmly planted in the direction of the past, even when it doesn’t appear to be (e.g. Jennifer Chan’s “Aryan Recognition Tool” app (2022)).

That this curatorial effort is not a very serious engagement with the problem at hand is evidenced by the Timeline along one of the long, white walls in the gallery, meant to show some of the key points on the trajectory of the white race as a concept. There is a strong American presence on the timeline, as it’s to be expected, but even I did not expect to see “the publication of Robin diAngelo’s White Fragility” at its apex.

Across the sidewalk from the Art Museum building, over in the Hart House, at the gallery that used to be known as Justina M. Barnicke Gallery, now the second venue of the U of T’s Art Museum, we find another exhibition which is also, effectively, about race. The Counter/Self (Jan 11-Mar 25) is, on first look, about the art of presenting and performing a self, a persona. This is the by now familiar stuff going at least back to Suzy Lake and Cindy Sherman, and I’m always up for it. But it’s all about ethnicity these days, and er ‘decolonization’, so the artists are largely of Amerindian ethnicities (with the odd Muslim trickster thrown into Quebec's alleged cultural monolith), performing, celebrating their ethnic belonging. Men in stilettos with great makeup contesting gender norms is fine, but how many Kent Monkmans does the Toronto gallery goer need in a year? Only the original one, I’d say, but to each their own.

The photographers in that exhibition that I enjoyed the most: Stacey Tyrell and Meryl McMaster (who is having a bigger retrospective at the McMichael as of Feb 4, though somewhat drearily titled Bloodline). It’s worth looking them up, especially Tyrell.

Other arts in February

Feb 9 to March 9: English at Soulpepper, about a TOEFL class in Iran, looks promising. TNY did a piece on the Iranian-American playwright Sanaz Toossi’s award-winning play about a year ago.

Feb 11, 7-9 p.m. The only new thing in a very long time on the seriously ebbing “indie opera” scene in Toronto is the Opera Revue. They’re back this month with an evening of arias called Debauchery at the Dakota and billed as an Opera Burlesque Review. This could be great or a disaster. Burlesque, aka Stripping for the Middle Classes, went out of fashion more than a decade ago for a reason so… on verra.

Feb 14, 7 p.m. at the Supermarket: Now that the elderly gay statesman Sky Gilbert is retired from teaching, he has time to create and run his own reading series. The Liars Club will give writers and poets 5 min to say what they believe needs saying - a fiction writers’ open mic of sorts. “We celebrate lies and liars here, and the ability to create strange, well crafted, impossible, horrifying and beautiful worlds with words.” Details here but scroll way down.

Feb 17: TSO’s Return to Massey Hall. Samy Moussa is always a treat and one of the most interesting composers around today; and what’s not to love about the Bruch Violin Concerto and Tchaikovsky 5. All this in a recently renovated Massey Hall. I can’t remember the last time a TSO announcement made me this giddy.

Feb 22, Koerner Hall: The always stylish in every sense of the word Emily D’Angelo performing a song recital. The program looks tremendously well thought-out.

Feb 24-25, Les corps avalés by the Compagnie Virginie Brunelle at the Harbourfront Centre. Music performed live on stage by the Molinari Quartet, though I do hope this tedious minimalism that we hear in the trailer won’t be the entirety of it.