Shed your old life with Constance Debré

plus Elizabeth Ruth's Semi-Detached, and a significant exec change at Toronto's Museums and Heritage

Would you blow up your life to rebuild it from different premises? Would you do it to answer your calling?

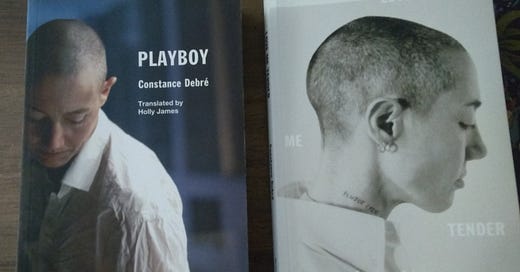

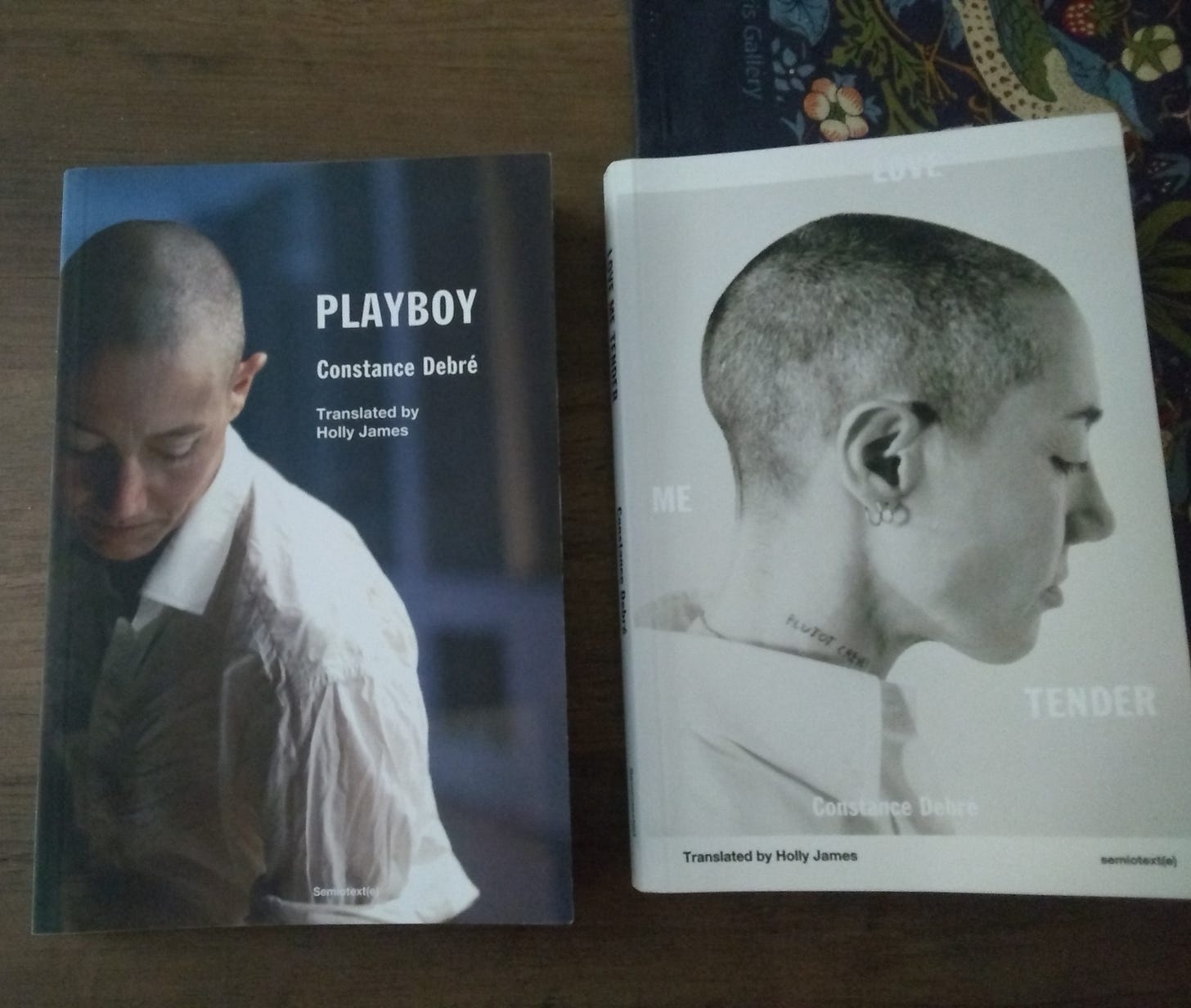

American publisher Semiotext(e) translated the two autofictions by Constance Debré in reverse order (maybe because Love Me Tender’s success called for the publication of its prequel) but read them as they appeared in French, Playboy (2018 (Eng. tr. 2024)) first and Love Me Tender (2020 (2022)) next. Both books are translated by Holly James.

Playboy is not about playboying but about tomboying, returning to the tomboy youth which the narrator abandoned when she set herself off to a normal heterosexual and career-oriented path. She is a criminal defense lawyer that has just left her husband and son, and is gradually lightening her work load so she can quit and live a monk’s life of almost no possessions, writing, swimming and, an unexpected item in aisle 4, no-strings attached sex with women. She is returning, she is certain, to her true sexual orientation. And to a life outside the confines of the couple.

In a slightly awkward interview with Chris Kraus in Granta last year, Constance Debré described the life change as “a bit like Saint Augustine and his conversion. In the same week, I had sex with a girl and I had the feeling that I could write. I had this incredible feeling that I could catch things, that life was there to be caught." This is beautifully put but perhaps a little too neat: her two memoir-like books are extremely carefully crafted to appear lean and unsentimental, the narrator in control, the self limpid and shedding everything extraneous. The book is close to the religious conversion narrative, the joining or the abandoning of a cult, but this damascene journey does not end in an extensive new belief system. It’s the existential paring down, not unlike Buddhism. The desire for women is honoured, but doesn’t rule her life. She is detached, in every sense.

We never learn if there was something specific that prompted the exit from the old life, and why the job that she spent many years qualifying for suddenly (was it sudden?) revealed itself as pointless. “Later I go to the cafe with some of the other parents. I listen to them all talking about the apartments they’re buying. They don’t seem happy. The guys are all bored and the women are worried about getting old. They all go to the same places on vacation.” When she moved out, she took with her a sofa, a bed for her son, a couple of pieces of clothing and very little else. From one book to the next, the narrator learns how few possessions she needs to live a life that she wants to live.

The complicating thing for all this leanness is that our hero comes from an old aristocratic and haute-bourgeoise family that boasts a prime minister of France and a bunch of landed (if under-earning) former aristocracy. A decaying castle with a moat occasionally features. When she can’t afford to pay rent even for the tiny bachelor’s she’s in, she moves to a friend of a friend’s who lets her live in his spare room for free. There is always somewhere she can crash. We are also led to believe that she, like her destitute gentry father, is penniless. She steals food from supermarkets, she cheats on train fares. The only earnings that are reported are “from the book”. An advance? No need to ask such petty bourgeois questions.

Both of her parents, her now late mother and her aged, chronically ill father, have been heroin addicts. She still visits him occasionally, and while he cannot accept that she prefers “girls”, they tolerate each other. There appear to be no other significant figures or friends.

Playboy has only two “girls” (the French “filles” is less sexist, and can apply to women of all ages), her first two relationships: one with an overpromising but underdelivering woman married to a man, and the other with a much younger woman who ends up being too attached to her and having expectations. By the end of the book she is already cynical about “girls” too and has been graced with insights into why men hate women. There is an extraordinary passage on p. 51 of Playboy which I can’t pluck out of the context without diminishing its meaning: helplessness before women, mixed with contempt. “I understood the violence of men.”