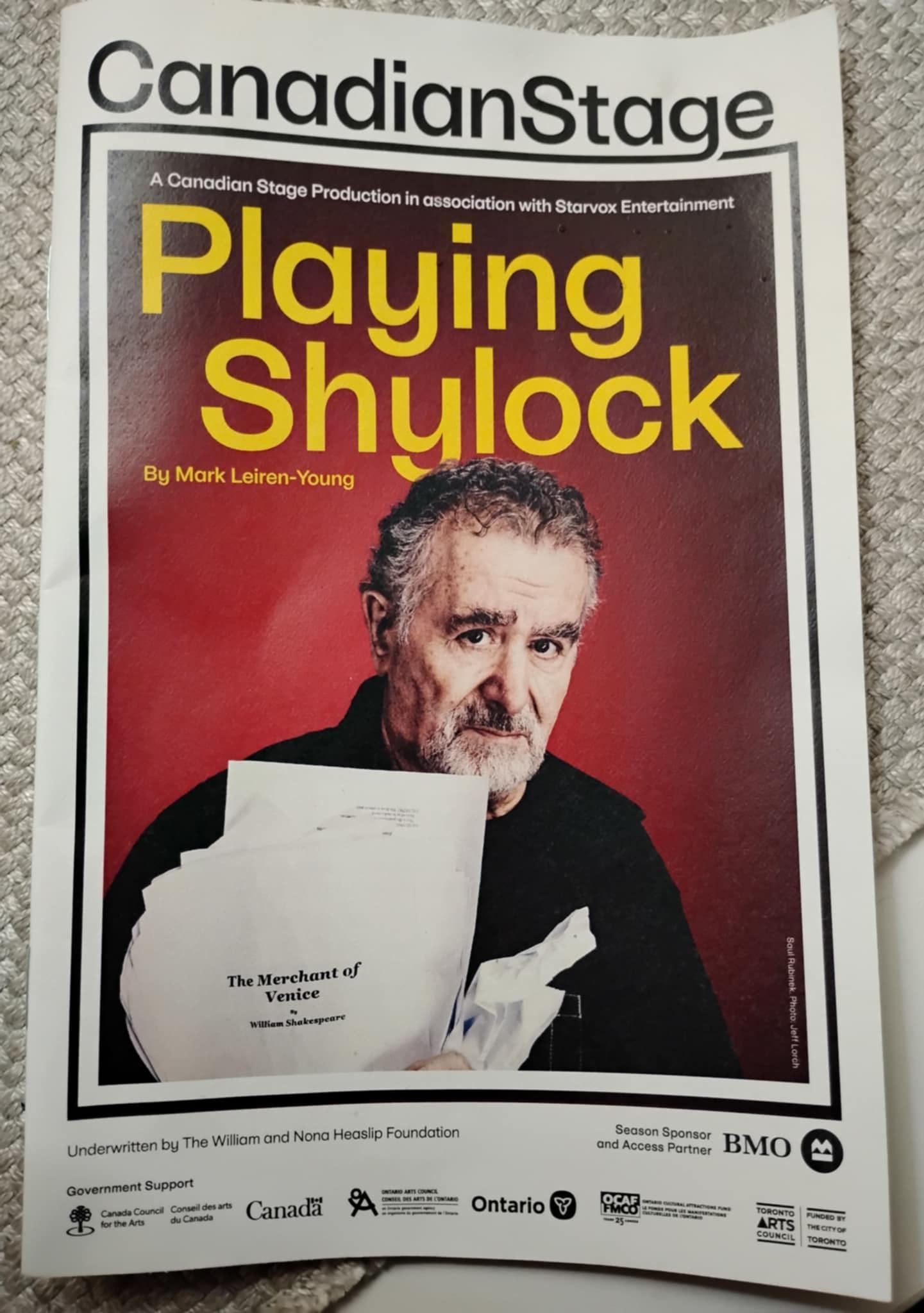

Is the character of the money lender Shylock in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice an antisemitic trope, or the first fully human Jewish character in English literature? Yes, resoundingly answer playwright Mark Leiren-Young and veteran actor Saul Rubinek in Playing Shylock currently on at Canadian Stage’s Berkeley Street Theatre. And we should keep putting it on.

The play is written as a monologue delivered to a disappointed audience by a lightly fictionalized version of Saul Rubinek after the CanStage production of The Merchant was abruptly cancelled due to protests. It is both personal, about Rubinek’s life and family, and also about the history of Shylock and Jewish representation in theatre arts. While not a small number of recent productions, worried about contemporary resonances of some of the verses, have presented Shylock as a member of another marginalized group or neutralized the Jewishness of his appearance, this imagined production that we are missing has gone all-in on Shylock’s ethnicity and religion.

And this was the character’s dream come true: to play Shylock dressed in clothes that his zaida often wore in his lifetime at the easternmost reaches of northeast Europe, and to honour his father, an AmDram enthusiast who wanted a chance to speak Shakespeare’s words in his mother tongue, Yiddish. The grandfather disapproved of his son’s wish to perform in plays—the domain of the ungodly scoundrel—but the present-day Saul finds a way to reconcile the two men. Posthumously to both, Saul gifts the father a sampling of Shylock in Yiddish and convinces the art skeptic that was his grandfather of the value of art and play - and how important it is to let it be free. Even if it offends.

Shylock was created, Saul reminds us, by employing and so perpetuating a noxious stereotype, but he’s also the character who’s given the following words:

—Hath

not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs,

dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with

the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject

to the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as

a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed?

if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison

us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not

revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will

resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian,

what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian

wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by

Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you

teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I

will better the instruction.

Before Shylock, Jews featured in English and other languages as stock characters, essentially some version of the devil. The most popular play involving a Jew before Shakespeare in Elizabethan England had been Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta in which the title character happens to be a mass poisoner (of Christians), pretty much evil incarnate. The audience at the Globe Theatre would have expected something similar in The Merchant, and would come well supplied with figs and oyster shells to throw at the villain (panto-like interaction with the stage was not discouraged in theatres). But hearing “If you prick us, do we not bleed? / if you tickle us, do we not laugh?”, Saul is certain, must have stayed their hand. One of the reasons Shakespeare’s plays are sometimes described as ‘novelistic’ was this feature of letting contradictory moral visions air themselves fully and inhabiting the minds of seemingly most peculiar people, and that way sneakily understanding their humanity.

And who played Shylock, in the history of reception of The Merchant? Why, the biggest theatre stars, of course, the minority of whom have been Jewish. And not only Shylock; recalling his time in Ontario’s Stratford Festival as a young actor, where he held a contract for minor roles one year and enjoyed a stable income, Saul ponders the then-total scarcity of actors of Jewish origin playing lead Shakespeare roles in Canada. In Hollywood meanwhile you could be a Jew running a studio, but not a romantic lead in a major movie, unless you de-ethnicized your name and your life (Rubinek quotes some of the most famous cases) and sometimes, er, your nose too. And today? Today, you could easily cast a Jewish theatre star as Shylock, except that The Merchant is programmed less and less due to its perceived antisemitism. The cries of which, you will remember, closed the current production too.

(I will interject here that there was at least one famous Jewish Shylock out of Britain, David Suchet’s. I caught a documentary about it long time ago, in which Patrick Stewart and Suchet analyze the character and approach it in their two distinct styles:

And recently there was the much-talked about production set in 1936 Britain with Tracy-Ann Oberman as Shylock (a slightly different proposition, granted, when he’s played as a beautiful middle-aged woman))

As much as Jewishness and Shylock, this play is also about the pesky issues nipping at the theatre and fiction of any kind these days: who’s allowed to play who, say what, evoke what emotions, under what context, and how do words harm. None of this is mentioned of course, but the play is very much about the circumstances surrounding the recent cancellations, withdrawals, and legal troubles many writers, directors and companies had to deal with, including the double cancellation of The Runner in Victoria, actors at Shaw refusing the say the n-word in character, other actors in another company refusing the say the word ‘savage’ in character and Equity taking their side against the director (who was later vindicated), a gay playwright’s piece being removed from the season because he didn’t like a trans memoir and said so on his personal blog, and the many many recent cases of limiting creative expression freedoms regarding indigenous content in theatre and other fiction.

Playing Shylock is clear where it stands on this: “I thought acting is being someone else”, says Saul in one scene, and goes on that acting, theatre, art are about inhabiting someone else, imagining how others are, stepping out of the I and me. After making the case for casting Jewish actors as Shylock, the play then gently dismantles it: there’s a very short step between “cast Jews as Shylock” to “only hire Jews for Jewish characters”. It happened with other minorities - gays too, notes Saul, remembering a handful of roles of homosexuals he played because actual homosexual actors hadn’t dared come near them. Today it’s different; but in this too, there’s not a large distance between “only gay actors should be playing gay characters” to “gay actors’ mission in the world is to play gay characters”.

In short, this is theatre by adults for adults. Don’t miss it.

(You can watch Saul Rubinek talk about some of this stuff in this recent TVO interview, which is VG except for the question “How do you learn all those lines”. Dear god. Luckily “Where do you find your ideas” did not feature this time.)

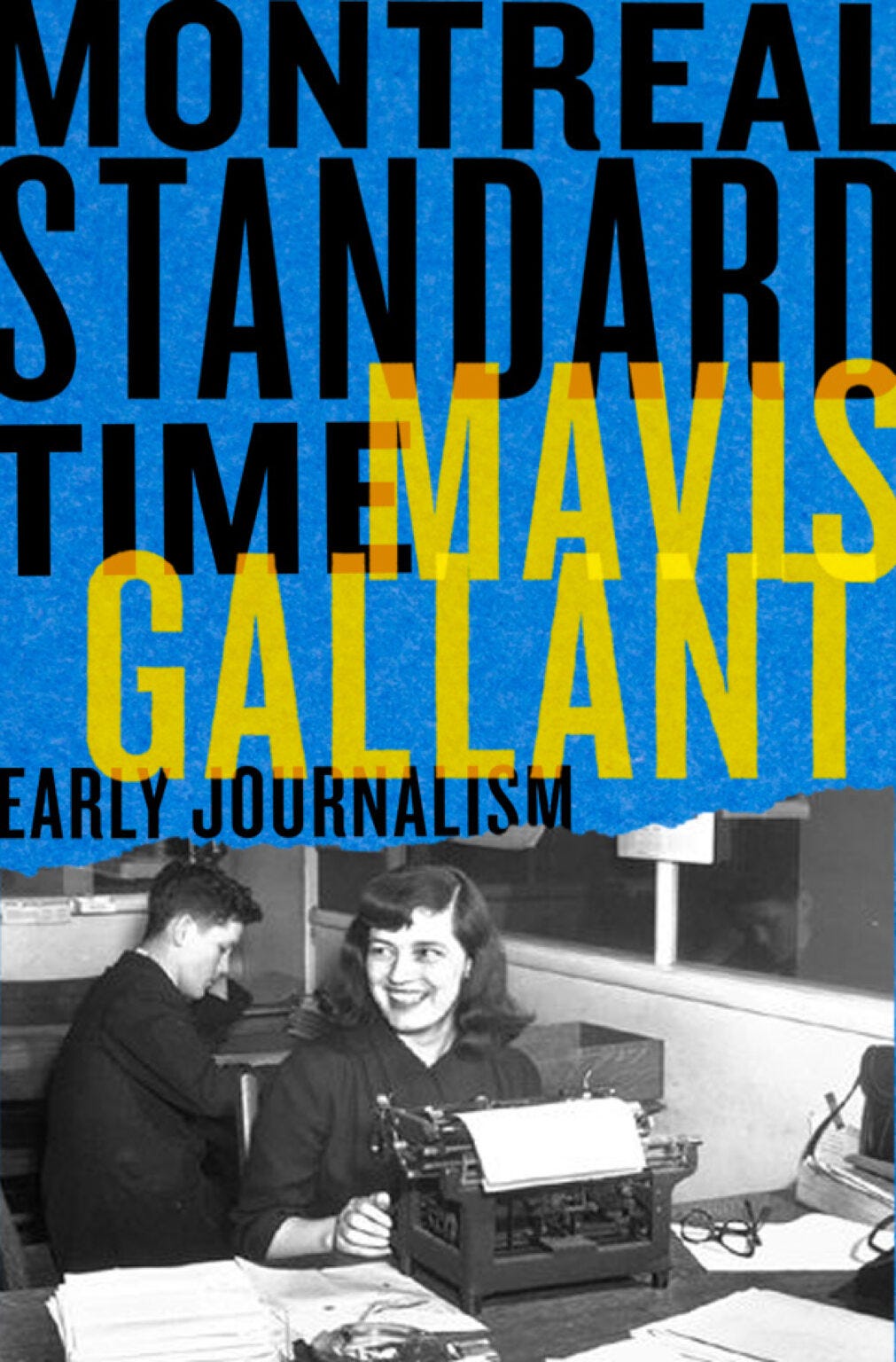

I was in the Hub again, this time writing about a lovely book of early journalism of one Miss Gallant, Montreal-based lady reporter during and after WW2. Read here.

Thanks for this! If you're interested, both Saul and Mark appeared on separate episodes of our podcast Re-Creative recently in which both referenced this production, which I wish I could see.

Saul's appearance: https://re-creative.ca/the-plays-of-edward-de-vere/

Mark's appearance: https://re-creative.ca/spider-man/