Talking paint dry

I made a mistake the other day of reading copy from an art gallery website. One of my favourite painters right now is the Vancouver-based Russna Kaur whose work can be found in several galleries in BC. So I was swiping the JPGs of her work on Google Pictures, it’s a very relaxing activity, there should be an app for that, when something caught my attention and led me to click the link to the Burrard Arts Foundation. A Q&A with the artist, excellent! Let’s see. Here goes; first question.

Er, OK? Reducing the artist to her ethnicity… reducing the history of abstract painting to the ‘white’ and ‘male’? Who is this copy for? The peers? The government funders? It certainly isn’t for art consumers, let alone those who never wander into a gallery. What is an art curious person without a graduate degree in humanities to do with this?

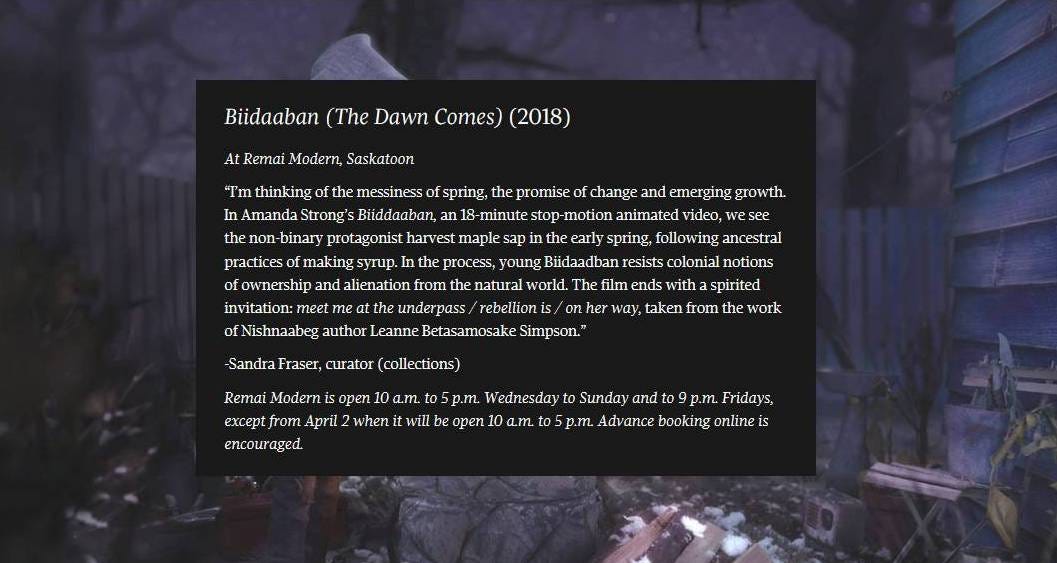

Art speak has been murdering visual arts for decades, and now we have another whammy coming for the arts from the same source, the academe: the woke identity politics. We’ve all encountered artspeak in support materials in exhibitions, in brochures, on labels, panels, descriptions. More likely in public galleries, interestingly – perhaps because part of the mandate of the public galleries and museums is to educate the public, but this is exactly the wrong way about it. There are several artspeak generators online, and some artists too are adding them to their ‘practice’ (make your own artist statement here). All this spills over into specialist art media and back when we used to have arts criticism, it influenced the mass media too. Here’s a recent… what is this, list copy? The Globe made a list of the newsworthy media/visual projects earlier this year, and this was one of the entries.

Woke bingo meets art speak. Is there anything sadder?

It’s not that I don’t understand artspeak. I sometimes even selfishly enjoy it. The references from critical theory, psychoanalysis, art history, Continental philosophy, I’ll drink them all. But these art speak intros, descriptions, Q&As are kind of onanistic and leave the vast majority of people behind. You had one job, copy: to seduce someone into becoming curious about a work of art or an artist, and you failed. When an artistic discipline becomes something that only people in the academe practice, interpret, preach, the bell has tolled for it. Poetry is somewhere in that stage now and conceptual and performance art as well. The importance of the MFA creative writing programs and residencies for fiction publishing is tipping the Anglophone novel in that direction, but it is not quite there yet, luckily. Photography and particularly painting are safe, I think. For now.

When I was starting out as an arts journalist a decade ago, I was primarily interested in visual and media arts – before opera steered me away permanently. I travelled for contemporary art (the way I’d later travel for opera). Most of my friends were from that world. I went to the Power Plant every other weekend. I dug out today the first piece that I wrote for C Magazine: it was about Hal Foster’s view on the avant-garde. What was it, is it alive, can it be alive again, what would it do today. It’s a fairly academic piece, as Hal Foster’s books, which back then married Marxism with Lacan, required. I didn’t think that job of someone who writes about the arts was to seduce someone into developing interest, perhaps even getting excited about some of the art. What was the job? To contribute to the high-level analysis, to use arts as theory fodder? Excitement, any un-analyzed emotion about art have at some point in recent history somehow dropped from the toolbox of proper art historians and theorists. Notoriously/famously, Camille Paglia often bangs on about this. When she was finishing her PhD, it was already uncool and unacademic to get too excited about art that one is studying. She of course claims it was because of the oncoming hegemony of deconstruction and feminism which dissect and warn instead of opening new venues of enjoyment for people, but I don’t know that that’s quite right. (Derrideans are a tiny minority in arts and comp lit departments, though feminism fares better.) Whatever happened, the academese massively spilled over into the art world, perhaps because of and with public funding. Sociological expectations definitely did come with public funding. (Art reduces crime in neighbourhoods! It bolsters the economy! Etc. All the way to: Reconciliation! Or, Decolonization!)

Can conceptual artists skip the academic-curatorial establishment? Julian Stallabrass wrote about the Young British Artists of the 1990s in this context: coming out of the Thatcher era, they were DYI-ers who did not wait for institutional recognition, grants, dues to be paid off but, how Stallabrass saw it, went directly to the media and to the donors, with loud, visceral, media friendly, what we’d now call click-baity, outrage-courting arts.

How is the conceptual art to come out of this clinch, I haven’t the faintest. On the one hand, the kiss of death of the academe. On the other, the virality, the sponsors, the media, the commerce. Both worlds now demanding a degree of political correctness.

And all this time, painting is quietly chugging along. The uncool, under-reviewed, old-fashioned painting. Something that, not at all subversively or ironically, people hang on the walls.

A favourite place to pass by on my walks, and on those rare non-lockdown days actually visit, has been this private gallery called Muse, near the Summerhill subway station. It only features painters and sculptors, most of whom are somewhere on the abstract continuum, and usually mid-career. Bizarrely, as much as 90 percent of their stuff I find affecting. It’s not the lockdown! I’ve looked at a lot of things, followed many a gallery on Instagram last year and a half. I spoke with the owner once and he told me the business has been brisk during the pandemic, as everyone wanted to make their homes more bearable.

Some months ago I too rearranged all the furniture – was feeling a bit like the books on my wall of shelves were about to engulf me. The book cases went to the far wall next to the kitchen, and the place opened up, there was even breeze between windows. Suddenly there were all these bare walls everywhere. I looked at sites online for beginner art buyers, among others Toronto’s Art Interiors, where I discovered Russna Kaur. I stayed the longest on art dot com, where I found Malevich again. What a brilliant man, how could I have forgotten! Four prints for me, thank you. Around that time I came across a book on some fairly obscure (outside Britain) British painters by a writer new to me, Christopher Neve. Was it someone on Backlisted Podcast that recommended him? In any case, after flipping through an ancient U of T copy, I ordered Unquiet Landscape: Places and Ideas in 20th Century British Painting (2020 (1990)) from Blackwell’s, opened it and experienced a jolt.

Who IS this man? Here was an entirely new way of writing about painting. Zero academese. Deeply intense.

Landscape painting has always been about what it is like to be in the world and in a particular condition. What is really important? Not the large events, or the plot that develops, but the day to day. Far better to think of life as a series of states of mind experienced in changing circumstances and in differing places than as something that always has to have direction. Landscape painting catches at those unexpected ideas and emotions that come, and so easily go, on days of no particular importance. It shows life not as a development but as a condition. How often have you sworn to yourself that this is the most beautiful day you have ever seen, on no particular day, on a day like, and yet entirely unlike, any other? This, in the end, is worth living for.

Right! First paragraph in the book, and we’re already on the question of the meaning of life. But what other question is there.

The painter goes through the land and sees what nobody else has seen because landscape painting comes from inside and not out. It depends entirely on who he is. Nature… finds its way into his imagination via all his senses; it becomes part of his spirit, and then, with great care and sensitivity, it may be brought back again by hand into the visible world and somehow recognized. Many of the artists in this book, whom I have asked about this, do not know how this happens. They have within themselves an unexplained ability to darken or lighten other people’s feelings through pictures.

And near the end of the introductory chapter:

Must we think of all landscape painting as subject to the often ludicrous esperanto of art history, or all landscape as designated national parks? Paintings are about feelings not rationality, about imagination not common sense. The best I can hope to do is to discuss some of the ideas that English landscape may have given rise to, and then leave it to you to look at the pictures, testing them against what you know of life and death.

Neve looks closely at the work of these mid-20th men and women, establishes their ties to the land they roamed in their lifetimes, employs what he’s learned about them and gathered in conversation with them, but the rapport that is key here is one solitude to another. Not group to group, identity to identity, period in history to another period in history. As is the case with novels, we look at pictures alone. This one-to-one, individual to individual, is an approach that strikes me as unusual in our age. Neve’s openness to emotions and contingency, his nominalism, and always always awareness of temporality, makes for a very exciting way of looking at paintings.

His lack of cool opened up a clearing. It invites a different kind of art writing. What would he have made of my favourite abstract painters? That’s a harder task, I think, writing about abstract paintings in Nevian manner. We’ll see. Maybe I’ll give it a try some time. Does Canada have a lot of interesting landscapists from mid- to end of 20th on? Another thing to look at.