The best book about on-campus MeToo Jacobins - and it's 30 years old

Helen Garner's The First Stone

The reason I didn’t include this book in my recent rave about Helen Garner is that it’s very hard to find. The Toronto city library has a single, non-lendable copy. If you’d like to attempt to buy it online, a third-party seller will pop up on Amazon and offer to dispatch it from Australia with a delivery date set for two months later.

I dipped into it at the library and couldn’t put it away. I read till the closing time, and returned another afternoon and then another, until I finished the last page of its afterword in which Garner responds to some of her critics of the first, 1995 edition. The book caused the greatest uproar among her fellow feminists, for Garner was an early me-too-overreach refusenik - or would it be more accurate to say, worrier. She was an early example of what will, post-2017, in the angloworld be known as the Old (School) Feminist Reminding the Exuberant Sisters of Due Process.

The case was, looking back at it from the 2020s, easy to be ambivalent about. A college professor is accused by two young female students of groping: one claims it happened late in the end-of-year dance, the other that she was propositioned in his office. Garner read about the case in the newspapers, after the students went to the police and media got hold of the story. Why on earth would the girls go to the police, she wondered; couldn’t they mock, rebuff, use the college complaint procedures, talk to counsellors, use any number of instruments of redress or retaliation not involving calling the police?

The accused professor, who is also Master of the University of Melbourne’s Ormond College, denies vehemently that any inappropriate behaviour happened. He gets dragged through the courts and is found not guilty but it becomes impossible for him to stay in the job and, it turns out, find any other university employment. His career is over within a couple of years.

On reading about his case, Garner sends him a vague letter of support which he, unbeknownst to her, copies and distributes at every opportunity. This act has the effect of cutting her off from the two young women who refuse to talk to her. Through their supporters and lawyers they describe any attempt to be interviewed by her as harassment.

Garner talks to just about everyone else touched by or present at the event, the witnesses at the late night student-teacher dance, the previous Master, the subsequent Master, the man’s colleagues, superiors, his wife, the university managers, Old Girls and Old Boys. Turns out the young women did turn to the internal procedure first, but found it too slow and ineffective.

They also, Garner quickly learns, have on-campus supporters who lobby on their behalf, talk to or block the press, likely even strategically leak what’s being said in closed-door meetings when it suits the cause. These are a group of women, all feminists, all refusing to talk to Garner and seeing her as a sellout and an enemy. (In the Afterword, Garner writes that due to legal concerns she had to anonymize the key figure as multiple women, so it’s not clear how many ‘supporters’ the young women had or if it was one female professor with considerable clout.)

The now familiar cleavages emerge: between older women and young, between older feminists and the new generation; between those who see no gradation of assault and those who do; between those who see beautiful young women as possessing considerable degree of power themselves and those arguing that those women too are only ever victimized; between those who see sexualization and eros as oppression waiting to happen and those who don’t.

The women won’t talk to Garner, though she is practically begging them to make their case to her. Persuasion is abandoned; either you get it and you’re with us, or we can’t help you.

Another division becomes prominent too: between the on-campus world and the outside world. Between those who fit and those who are goofs.

The Melbourne University is, thank you British Empire, a sort of southern hemisphere replica of the University of Toronto. Divided in colleges, each with its own culture and teams, rituals of belonging and allowable drinking and partying levels, U Melbourne is one of the most prestigious and oldest schools in Australia. Ormond College will bring to mind U of T’s Trinity College. The dining hall, which I copied from Ormond’s Instagram, may ring a bell or two.

The head is called Master (at Trinity it’s Provost). The job consists of a combination of administrative, academic and branding duties: Master is a college mascot in so many ways, representing its people and aspirations. It becomes obvious to Garner, as she talks to the Ormond-men and -women, that Master accused of assault has never really fit. He was too informal, too available, prone to wearing the wrong kind of clothes on important occasions. He was never really a genuine Ormond man, and Garner wonders if that is why he was so easily dropped by the administration.

She also goes some way into the history of Ormond and the kind of college education which, until fairly recently, had excluded women and by institutional, cultural inertia, in some ways still did in the 1990s. She talks to female academics who have been interviewed for teaching jobs at Ormond and who found its culture insular and self-regarding. Wherever there’s an unofficial “one of us” culture in an organization (and cf. Vienna Philharmonic, for example), women will be seen as oddities in certain positions and will have to go the extra mile.

All that said, Garner doesn’t end up agreeing that the two women whose breasts were allegedly cupped by an authority figure experienced, by this act (if it indeed happened, and she doesn’t close the door on the possibility) and institutional indifference to it, irreparable harm. She is of the generation of feminists who broke the law to drive women to safe houses for illegal abortions; generation that created first women’s shelters. They can’t not see the gradation of violence. Not everything merges into the big blob of oppression which reduces young, capable women into bundles of helplessness.

I archived so many pages of this book, but I’ll try not to go overboard here and share just a few passages.

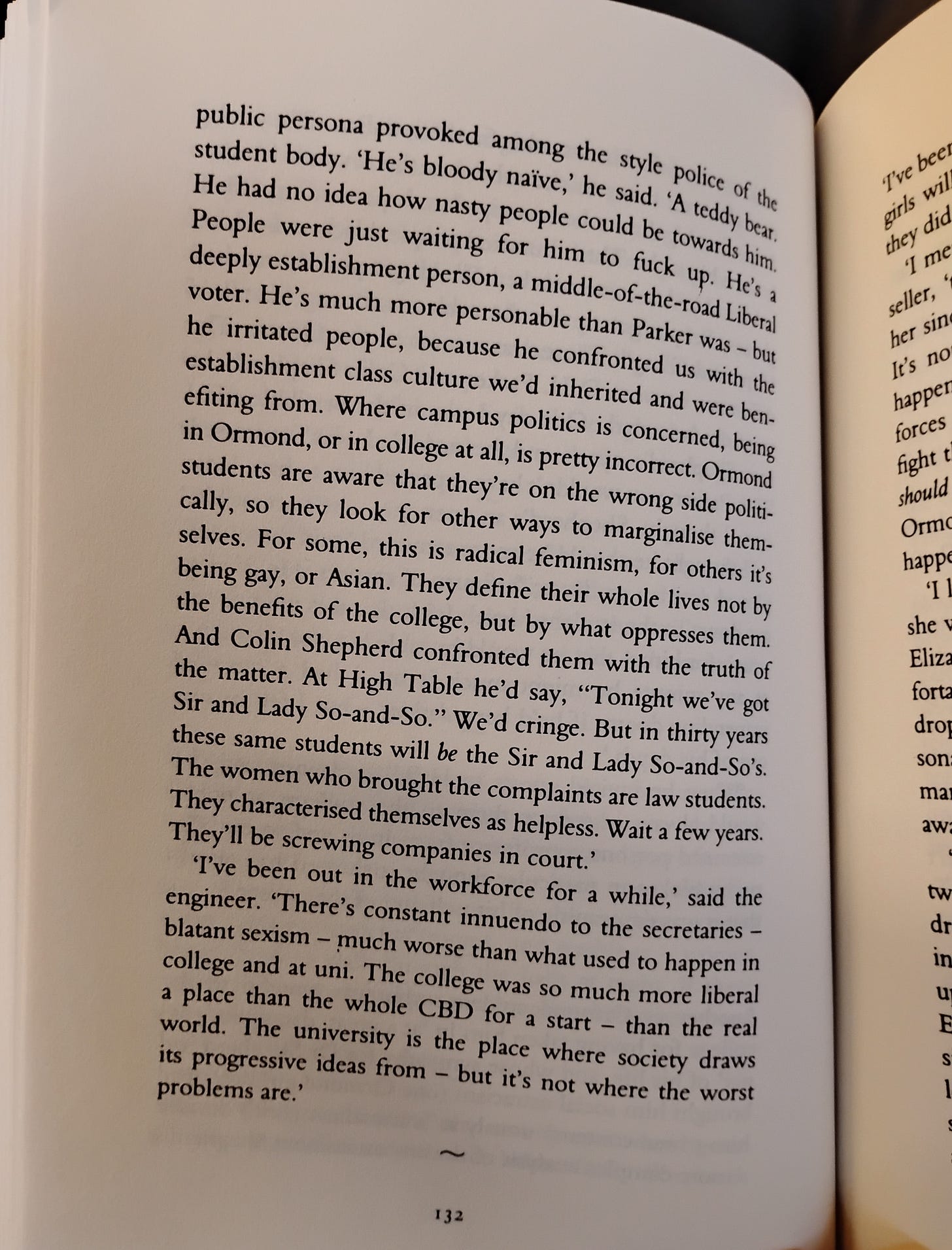

Why do students in elite colleges have radical politics? Overcompensation for being by birth of the establishment class, in essence. “Ormond students [insert here: Harvard, Columbia, U of T, go to town] are aware that they are on the wrong side politically, so they look for other ways to marginalise themselves… They define their whole lives not by the benefits of the college, but by what oppresses them.”

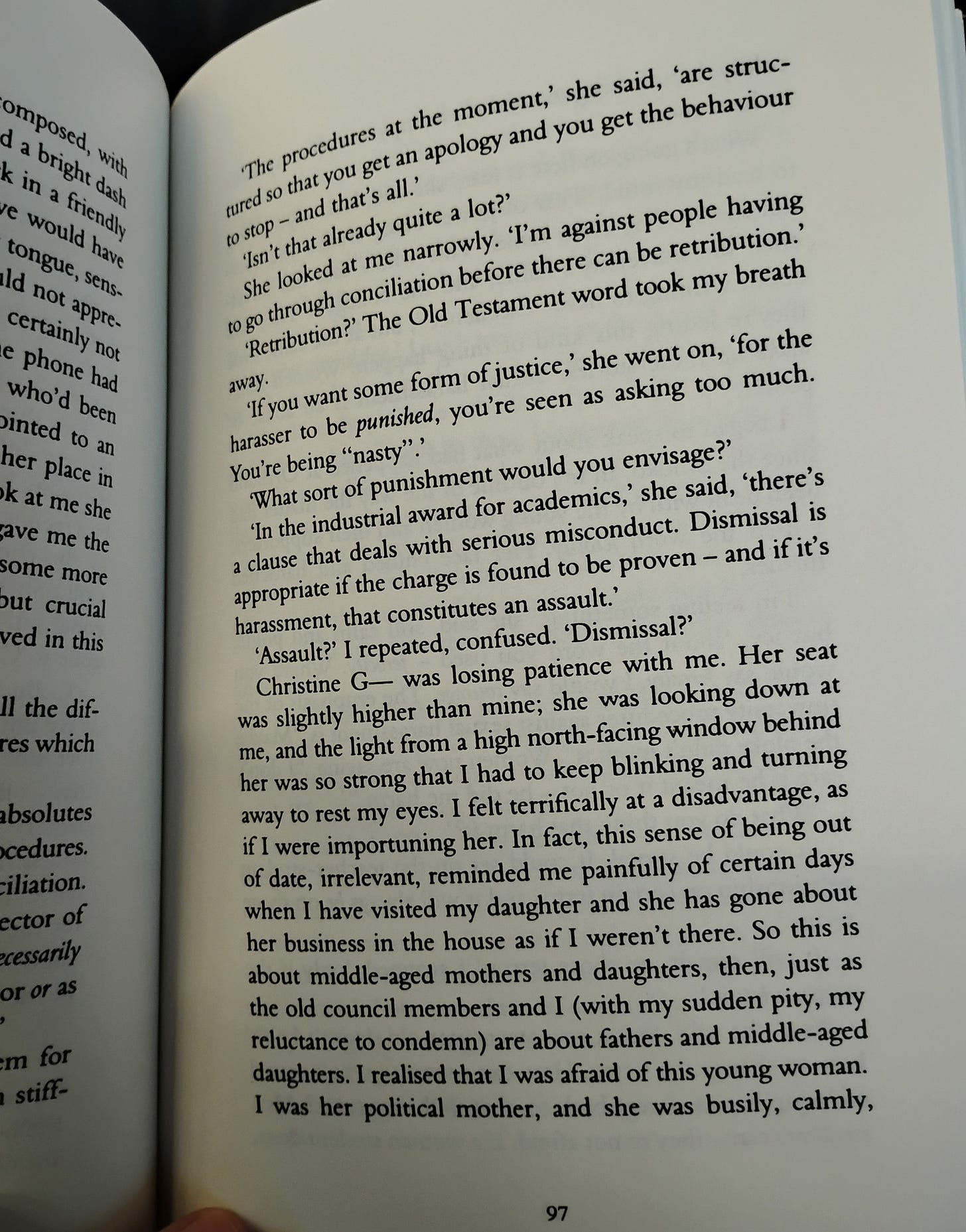

One of the young radical women finally agrees to speak to Garner. She is a lawyer and can carry an argument without excessive emotional involvement. They disagree on everything, but part ways amicably - which is atypical in this book:

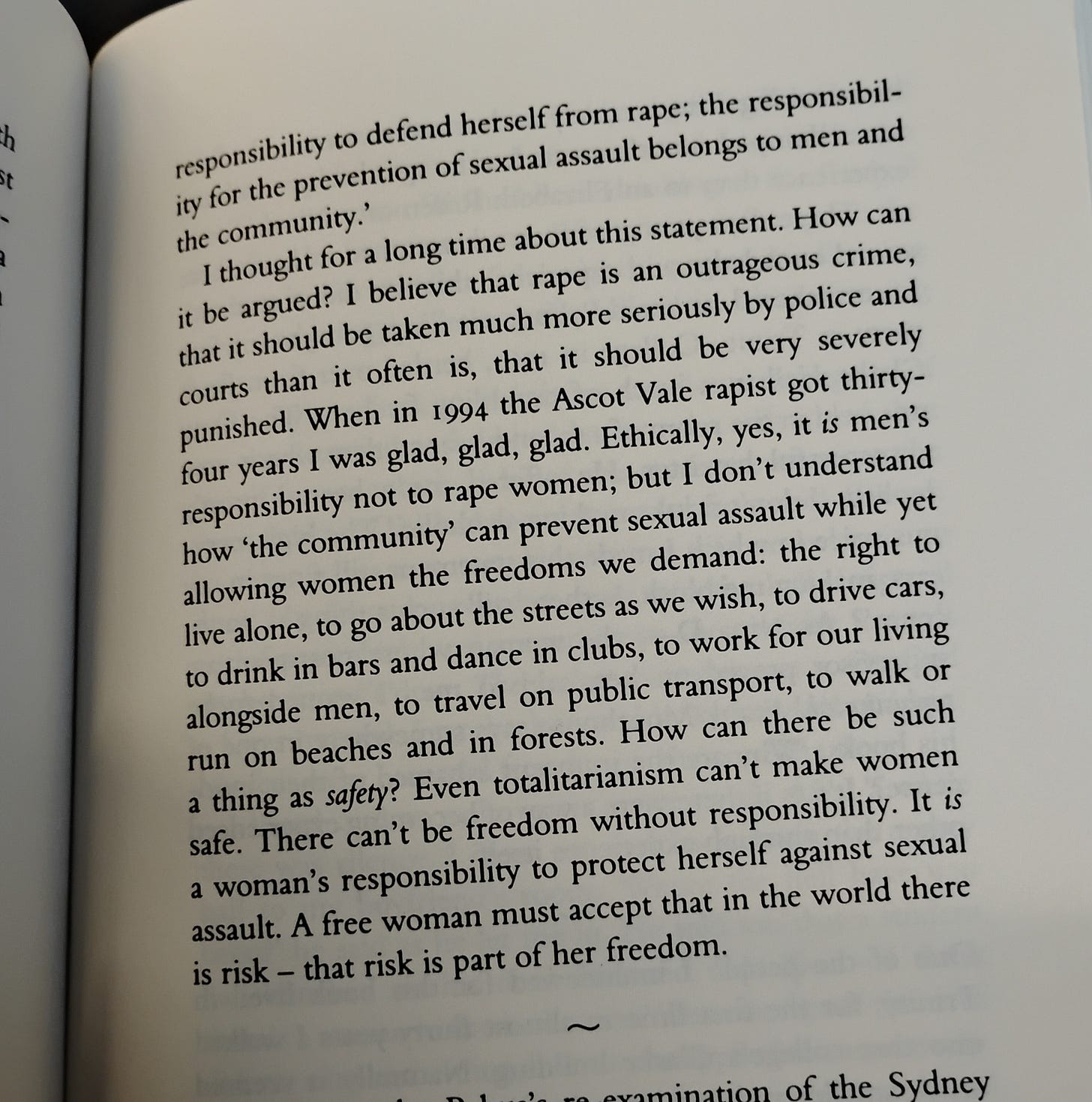

“How can there be such a thing as safety? Even totalitarianism can’t make women safe.”

“…they are offended by the suggestion that a woman might learn to handle a trivial sexual approach by herself, without needing to run to Big Daddy…”

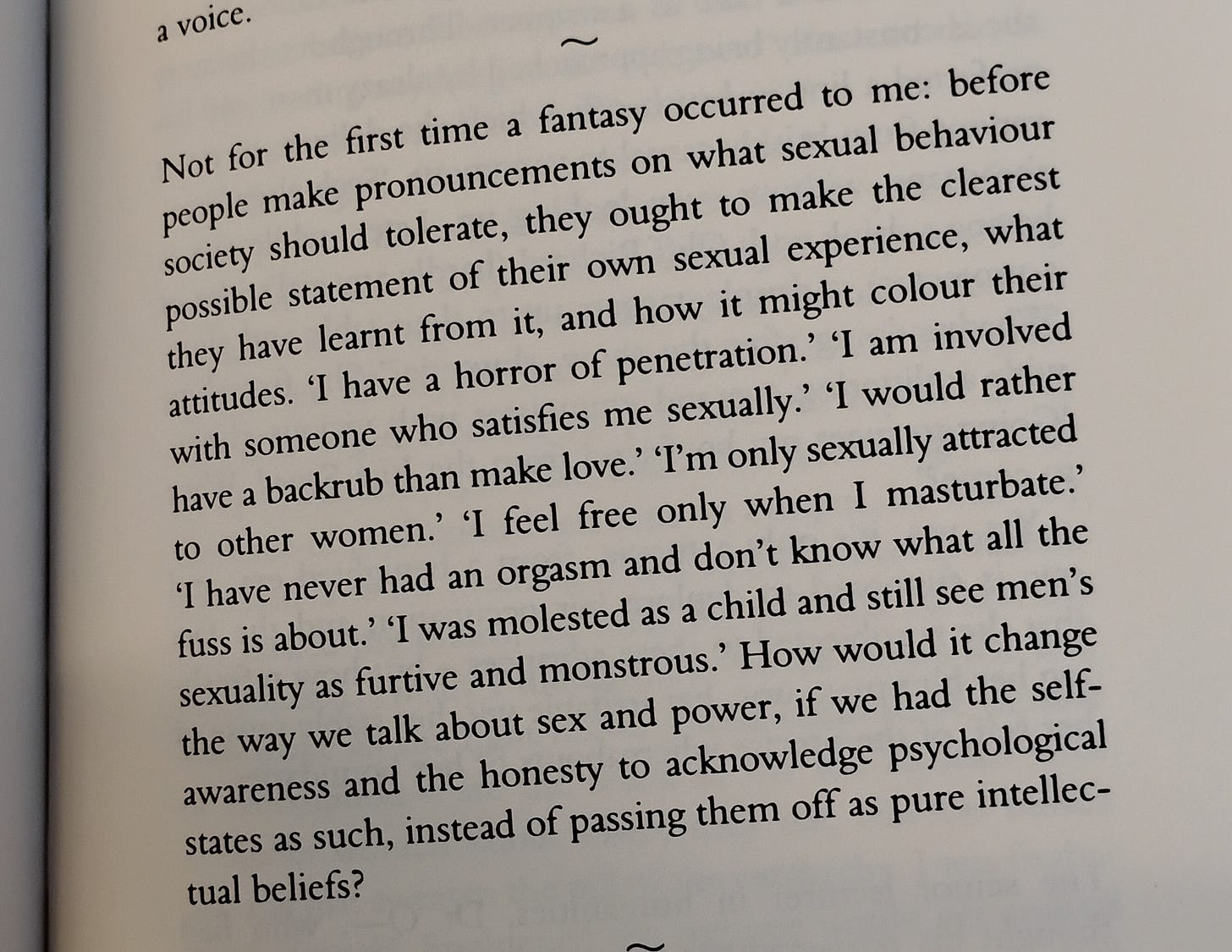

“…a fantasy occurred to me: before people make pronouncements on what sexual behaviour society should tolerate, they ought to make the clearest possible statement of their own sexual experience, what they have learned from it, and how it might colour their attitudes. […] How would it change the way we talk about sex and power, if we had the self-awareness and the honesty to acknowledge psychological states as such, instead of passing them off as pure intellectual beliefs?”