If Fernand Braudel wrote about the Mediterranean as one historical unit, Tony Judt took Europe as one vast and messy country, Claudio Magris imagined the Danube as a culture (albeit, in his vision, one that is heavily weighted towards its Austro-Hungarian end) – then why not the history of the Adriatic Sea as one entity? Historian Egidio Ivetic takes this approach in the newly released History of Adriatic: A Sea and Its Civilization (Polity). I haven’t had a chance to read more than this review, but the idea is an intriguing one if full of contradictions.

Is it the one, Adriatic civ, or is it a proliferation of civilizations? Do we still use the word civilization anyway? The argument is I expect that any civilization that made it to the shores of the Adriatic, any group of people between the Illyrians to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, had to adapt to the geography and the preexisting conditions to a degree. The argument is that the Adriatic has its own ways.

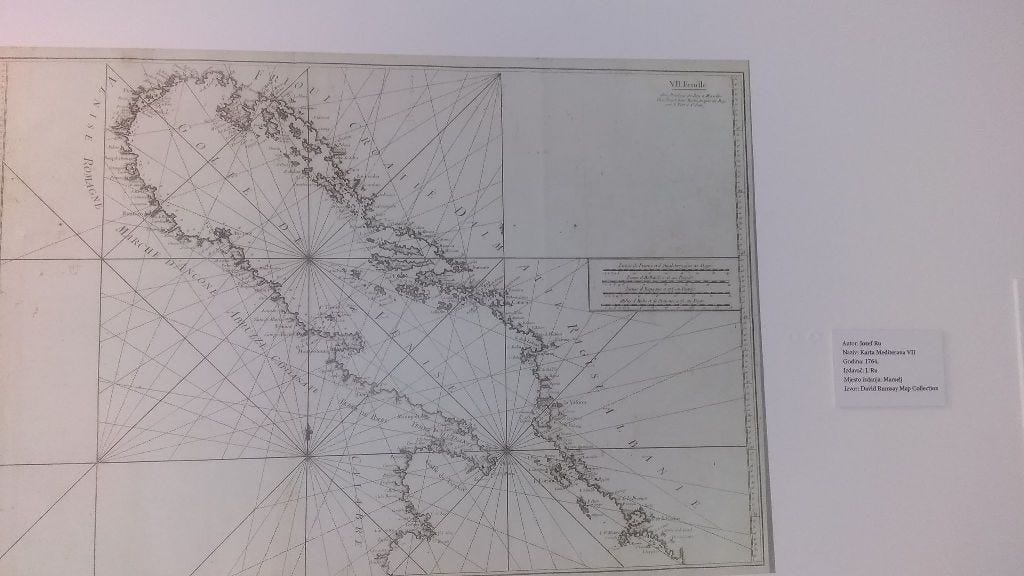

In its early history it’s easy to see the Adriatic as one entity: it’s the small Greek trading colonies on both sides, in today’s Montenegro as well as today’s Southern Italy, but the unity of the two sides got established and cemented by Rome, which easily occupied both coasts and much else besides and during which era the sea was known as Mare Nostrum (“Our sea”) – a moniker to be revived by Italian irredentists and fascists in the twentieth century. Diocletian was the Roman emperor from the other side of the mare, the province of Dalmatia, leaving in Split, today’s Croatia, a palace/garrison that is one of the biggest tourists attractions in the region.

The empire eventually split in eastern and western and then later disintegrated and numerous tribes, Goths, Visigoths, Celts, roam or settle either side. The Slav hordes only make it to the east coast; the Italian peninsula proceeds into the medieval age with its own ethnic mix. The eastern side of the Roman empire persists as the Byzantium and the Slav and Vlach and mixed Illyrian and who-the-hell-knows tribes shape their own statelets around it. What comes next to culturally and politically unify the Adriatic is the Venetian Republic, which dominated both coasts until well after the Ottoman invasion brought end to the Slav states and the Byzantium. Montenegro, where I’m writing this from, prides itself of “never having truly succumbed to the Ottoman yoke” but while the 200-ish-year occupation and colonization is probably the shortest one in the region, the geography of Zeta / Montenegro was so perilous, its economy so basic and the guerilla resistance such a nuisance that the Ottomans a lot of the time couldn’t really be arsed to collect all the levies due. For various periods it was an on-and-off occupation, it seems, but nation states did not exist and what we call sovereignty today would not be appearing in that familiar form in 1400s. Today’s Croatia and Slovenia fell under the Holy Roman / Habsburg Empire / Austria-Hungary and stayed there practically until end of World War One. South of there, it gets complicated. There’s a series to be made, the Netflix kind or a series of historical novels, on the fifteenth-century rulers of Zeta esp Ivan Crnojevic whose country was squished between Venice and the Ottomans. He challenge was how to play, cajole, ostensibly obey - one against the other. Venetians alternately fought him (over coastal towns) and plied him with nobility titles (when he was a useful foil to the Ottomans). His son and heir strategically married daughter of a Venetian nobleman, but his other son was, no other way to describe it, gifted to Ottoman Empire in Constantinople as a “guarantor of piece” where he converted to Islam and honoured his Albanian uncle by taking his name, Skenderbeg. Right, did I mention that Ivan Crnojevic’s mother came from the Albanian Skenderbeg stock? We think we invented multiculturalism in the twentieth, but it invented us, long time ago.

When Venice was dominant, the sea was known as the Gulf of Venice.

With the fall of Venice (which Napoleon’s conquests put paid to; ditto the city state of Ragusa/Dubrovnik), the Adriatic is in the divisive grip of Austrians/Austro-Hungarians, Italian states and Ottomans and from then on it’s centuries of disunity as the nation state rises. In Montenegro it’s now time for the bishop-warrior Petrovic dynasty, which is culturally devoted to Russia way more than the sea. But bit by bit, by the time of Nicholas I Petrovic, the southern border returns to the sea. The new formed nation of Italy however will hold a lot of the east coast of the Adriatic till its defeat in the Second World War, which left the swaths of Italian people chagrined by the loss of the mare nostrum. One of the best episodes of The Rest is History podcast is the show on Gabriele D’Annunzio – his charisma, his early invention and modeling of fascism, his rule of the city of Rijeka. The guest is Lucy Hughes-Hallett who talks about her D’Annunzio bio The Pike: Gabriele D’Annunzio, Poet, Seducer, and Preacher of War. The feelingz of aggro among the Italian population were real.

From WW2 on it’s mostly quiet distrust and weariness between the Yugoslavs, the Albanians and the Italians across the Adriatic sea, but it’s also the Pax Americana, the holidaying boom, the post-war prosperity, and Yugoslavs’ own kind of socialism where annual shopping sprees to Trieste or Bari were not unheard of among the middle classes. Ivetic’s book ends with the disintegration of Yugoslavia and the Serb-led federal Yugoslav Army shelling of the city of Dubrovnik in the newly independent state of Croatia. Much has happened since the 1990s, however. Nato memberships, you could argue, is what unifies the countries on both sides of the Adriatic sea. But Italy, like many other countries of the developed world, has seen a resurgence of populism on the right and is expecting a Georgia Melloni premiership. The post-Yugoslav countries across the sea are caught in effectively one-party societies: communists toppled and a formally multi-party system in place, but one powerful party, often of the nationalist populist kind, keeps winning the seemingly free elections and holding all the instruments of power. (See also under: Hungary, Poland.)

There is also a social history to be written of the recent Adriatic. James Joyce in Trieste. Dasa Drndic’s Trieste and Istria. The workers’ and pensioners’ holiday resorts along the Adriatic coast in communist Yugoslavia. The two Italian public broadcasting channels which at least two generations of Slovenian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Albanian kids grew up with and learned Italian from. (There were only three other, Yugoslav, TV channels so you were bound to turn to RAI UNO and RAI DUE.) And this is grandchildren of the people who have fought against the Italian occupation in WW2, gladly acculturating! (I was one of them.) The San Remo festival. The post-communist overdevelopment of Montenegrin towns. The Russians! Then suddenly way fewer Russians. Peter Munk’s revitalization of Tivat. (He seems to have been genuinely interested in Montenegro; his connections helped return some letters of historical import by two of the King Nicholas’ daughters to a local museum.) Infuriating traffic in the summer. The EU-ends-here border between Croatia and Montenegro. Over on the Italian side, Fellini’s Rimini. The Bar-Bari ferry (RIP; the opening up of the markets closed that one down). The Bar-Belgrade rail line. The Franciscans of Kotor. Et so many ceteras.

See you all soon; September is sooner than we know -

L.P.