In the last newsletter I invited readers to submit their favourite reads of 2022. Here are first two contributions. Keep them coming!

Alykhan Velshi: Saxons and Dreyfus

Kazuo Ishiguro, Buried Giant: This is not among his most celebrated or well-reviewed novels, but it is by far my favourite - I think beating out Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go. Set in post-Arthurian England, in a period of history about which we know little other than that the Saxons emerged victorious over the Britons, it tells the story of a mist of forgetfulness that’s come over the land, and an elderly Briton couple who set off on a quest to find their long-lost son amidst this mist. As their quest merges with that of a Saxon warrior trying to eliminate the source of the mist, the novel explores themes like ways of dealing with trauma in the past; are there things better off left unremembered; and can love exist without a basis of shared memories. Even though there are fantasy elements, it is not a fantasy novel. What it is though is lyrically written, elegiac, and sad.

Robert Harris, Officer and a Spy. A historical fiction thriller about the Dreyfus affair, told from the perspective of a French military intelligence officer, who was as anti-Dreyfus and anti-Semitic as any other, tasked with uncovering evidence to confirm Dreyfus’s guilt, but who instead learns the opposite. And what he does with that information. A thriller whose ending is already known but which I still couldn’t put down as I couldn’t wait to see what was going to happen next.

Stevel Ratzlaff: Two cheers and a raspberry for liberalism

Pragmatism as Anti-Authoritarianism by Richard Rorty, 2021. A series of lectures given in 1997 and only published last year, this book is Rorty’s last major work of philosophy. In the ten years he had remaining, he devoted himself to books meant for a general readership, celebrating and defending liberal democracy in the United States. (See Achieving our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth Century America and Philosophy and Social Hope.) The last two chapters are quite technical, but the rest is great provocative fun: “There is nothing to my use of the term ‘reason’ that could not be replaced by ‘the way we Western liberals, the heirs of Socrates and the French Revolution, conduct ourselves.’”

The Once and Future Canadian Democracy by Janet Ajzenstat, 2003. As someone who is unable to locate himself on the left-centre-right continuum, I found Ajzenstat’s substitution of liberalism/romanticism for that continuum, an elegant way of better understanding myself and the world. What higher praise for a book!

Ajzenstat strenuously advocates for liberalism as the birthright of Canadians. With attention to the Confederation Debates, she demonstrates that the proponents of Confederation were arguing from John Locke’s position: “What Locke proposed in brief was to remove from the realm of politics and public administration all of humanity’s dearest objectives, everything closest to the human heart: love of God, love of family, pride in one’s particularity. He proposed in short to take the romance out of politics.” In recent years our politics have been swamped by romanticism, making this book’s argument even more urgent than when it was published.

Ivan Illich: An Intellectual Journey by David Cayley, 2021. Starting with his breakout hit, Deschooling Society (1970) and until his death in 2002 Illich was cogently sharp in his criticism of what he called the “liberal fantasy.” David Cayley gives an incisive commentary on Illich’s ideas and their development. In the end Illich came to see liberalism as the corruption of Christianity, that the Church was “the chrysalis from which modernity hatched.” Throughout his life Illich drew attention to what he called liberalism’s war on subsistence. “Subsistence, for Illich, meant to stand on one’s own feet, to be able to speak in one’s own voice, and to be free of disabling dependence on commodified goods and services. To call this stance independence would probably be misleading because of the powerful overtones of individualism on that word. Illich could as easily be said to be in favor of dependence inasmuch as he was willing to rely on the fitful and unreliable charity of the other rather than replacing it with the guaranteed response of impersonal systems.”

And by me, two short reviews

Sometimes you read two books in a row that end up rhyming.

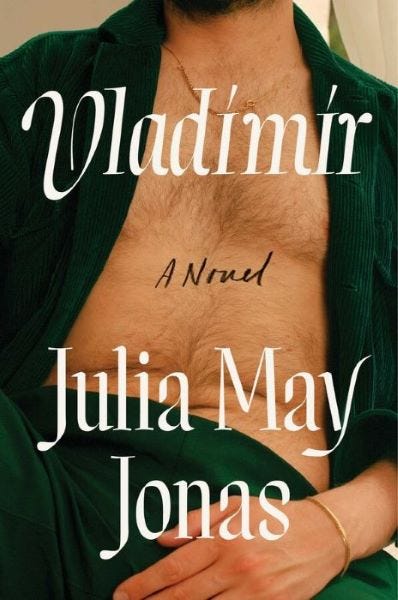

Julia May Jonas’ Vladimir tackles the newly absolute prohibition of sexual relationships between university professors and students in American universities through the eyes of a witty and cynical female narrator whose husband is under investigation for the trysts that took place in the previous era, when the teacher-student dating wasn’t verboten. They are both literature professors at a respectable non-Ivy League college, he the department chair, and find their open marriage suddenly out of step with the general atmosphere. “I wish [these young women] would see themselves not as little leaves swirled around by the wind of a world that does not belong to them, but as powerful, sexual women interested in engaging in a little bit of danger, a little bit of taboo, a little bit of fun. With the general, highly objectionable move towards a populist insistence on morality in art, I find this post hoc prudery offensive, as a fellow female.” From the very first page we’re in company of a narrator who’s astutely perceptive, though only about some of her own failures and vanities. Enter the new faculty member, experimental novelist of Russian-American descent, Vladimir Vladinski, the narrator’s latest erotic obsession. He is married, which does not at all derail our narrator’s plan to… do with her object of desire what Charles Arrowby in Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea did with his. (This isn’t a spoiler if you haven’t read Murdoch’s Booker winner, which btw everyone should.) I won’t say too much but the ending is surprisingly conservative, the older couple receiving an operatically magnificent form of punishment. Fine, punish them but don’t take away her book in progress, I pleaded with Jonas throughout the last few chapters, but to no avail.

Annie Ernaux, Getting Lost (diaries 1988-1990), translated by Alison L. Strayer

I could swear that I’ve read one of the lesser known works by AE (was it The Possession?) years ago but it’s completely gone from memory. Sometimes books find you at the wrong time and you get nothing from them. Getting Lost finds me at a more opportune time. It is the diary that she kept during the affair with a married Russian diplomat, the event which received literary treatment in her novel A Simple Passion. The diaries are raw, frequently TMI, and seem to be minimally edited. A lot of it hasn’t aged well, especially in the first half. Russian and Eastern Block women, including her lover’s wife, are more dumpy and “sturdy” in comparison with the thin and fashionable Frenchwomen, we learn. She also despises the people that come to her book events (“I don’t write for you!” she’s dying to scream at the women who’ve come to hear her talk in Sweden). We learn about the couple’s love-making positions in anatomic detail, and they’re all very, how shall I put it politely, male-focused. The repetitiveness of the damn thing – when is he going to call? It’s been 4 days… 5 days… a week… 8 days… he called last night! – is tedious. But then, somehow, this whole sorry thing grew on me. She’s highly perceptive on the ebbs and flows of desire, on getting to know another’s body. The man whose father was decorated by Stalin, as he likes to point out, often leaves her apartments taking with him packets of Marlboro and bottles of whiskey, giddy like a child out of a toyshop. He tells her he loves her only once, but she reasons it was during sex so she shouldn’t take it seriously. (And rightly so; outside the bed, he tells her he’ll only ever love his wife.) Their liaison ends when he is re-posted back to the USSR, now fast disintegrating after the fall of the Berlin Wall. He never phones to say the final goodbye and simply disappears without a trace. Her response (or shall I say revenge) will be writing. In a cold light of the post-abandonment, she realizes she was “playing the role of ‘extra’ in my own life for the entire year.” The last fifth of the book is the most compelling: the moment by moment reconstitution of the self that existed before Sergei. Final entry: “For the first time since November 6 (the last time I saw S), I waken with an inexplicable feeling of happiness.[...] There is this need I have to write something that puts me in danger, like a cellar door that opens and must be entered, come what may.”

And an ICYMI: in the last dispatch I reviewed Joanna Hogg’s film The Eternal Daughter. There’ll be a couple more newsletters before end of year, so send those book reccos so I can include them.