One of my lucky Little Free Library finds in recent weeks has been a DVD of A Touch of Class, the 1973 film with Glenda Jackson and George Segal which the internet describes as a romantic comedy. It’s far from the genre - unless we think of the 1970s rom-com as its own, more realistic sub-type. I’ve seen the film a lifetime ago, as a young person, and thought it was mildly amusing but not an essential entry in the GJ canon. Watched in my advanced middle age, this is a very different film.

A recently divorced mother of two has a silly meet-cute with a married American in London, and they go out for dinner. From the very start their conversation is knowing and adult, of the kind that you can’t imagine finding in any recent mainstream movies (Melvin Frank and Jack Rose co-wrote the script, based on Melvin Frank’s 1960 film similarly built around a middle-aged couple trying to have an affair by embarking on a disastrous trip). Steve is attracted and it’s not his first time at the rodeo – he immediately comes out to her as someone who’s never had an extra-marital affair… while his wife is in the same town. Vickie is looking for an affair, an experience, and to be desired and liked again, but has no greater expectations and does not take him too seriously.

During their meant-to-be-romantic trip to Spain, everything that can go wrong goes wrong. After overcoming the hurdles, they do end up making love, but - this is a film for adults - while he seems to be ecstatic about the experience after, she is more sedate, explaining to him that “it’s different for women”, the ecstatic part doesn’t come on the first night but only after they’ve gotten to know the new lover. (Again, imagine this conversation in a contemporary rom com.) Another couple that Steve knows is in the same Malaga resort and Steve and Walter (Paul Sorvino) have conversations about the difficulties of having a moderate affair and what to do if it turns into something more serious.

After the largely comic opening, the film goes comedy-turning-serious-ish, as the two lovers rent a flat in Soho -- then a seedy underbelly of London – where they could meet and spend time together. Vickie’s children are never in the picture, and there’s never any question of guilt of having to find sitters, sometimes for overnight stays, though it’s possible that this side-issue never occurred to the two male screenwriters. Still the lack of guilt-tripping is refreshing; a number of novels set retrospectively in the 1970s and the “sexual revolution” days darken the era - Rick Moody’s The Ice Storm (written in the 1990s, set in 1973) comes to mind, where the character who in Ang Lee’s eponymous movie is played by Sigourney Weaver and who has an affair gets a storyline in which her child dies in an accident. Tessa Hadley’s recent Free Love, set in the same era, avoids this trap while also avoiding the lionizing of the 1970s.

There are some hilarious scenes with Steve leaving the symphony (it must have been Mahler) to meet with Vickie in Soho for a quick cuddle and a bite, then running back to return to the seat next to his wife for the final movement. But things get less fun with many cancellations due to Steve’s family obligations, dinners gone cold, dates postponed or missed. GJ also played the “second woman” in another quintessentially seventies movie, Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971, dir. John Schlesinger, written by Penelope Gilliatt) and both films end similarly, when, after the triangle has flexed and stretched the duogamy as far as it was possible, the GJ character decides that “I’ve had it with this business, Anything is better than nothing. There are times when nothing *has* to be better than anything.”

More of the dialogue:

Bob (the young love interest that Peter Finch and Glenda Jackson share, played by Murray Head): “Look, I know you feel you’re not getting enough of me, but you’re getting all there is.” Alex (GJ): “Well, you’re spreading yourself a little thin, aren’t you.”

Also Alex, in a later scene: “Sometimes it takes a long time to understand how we feel.”

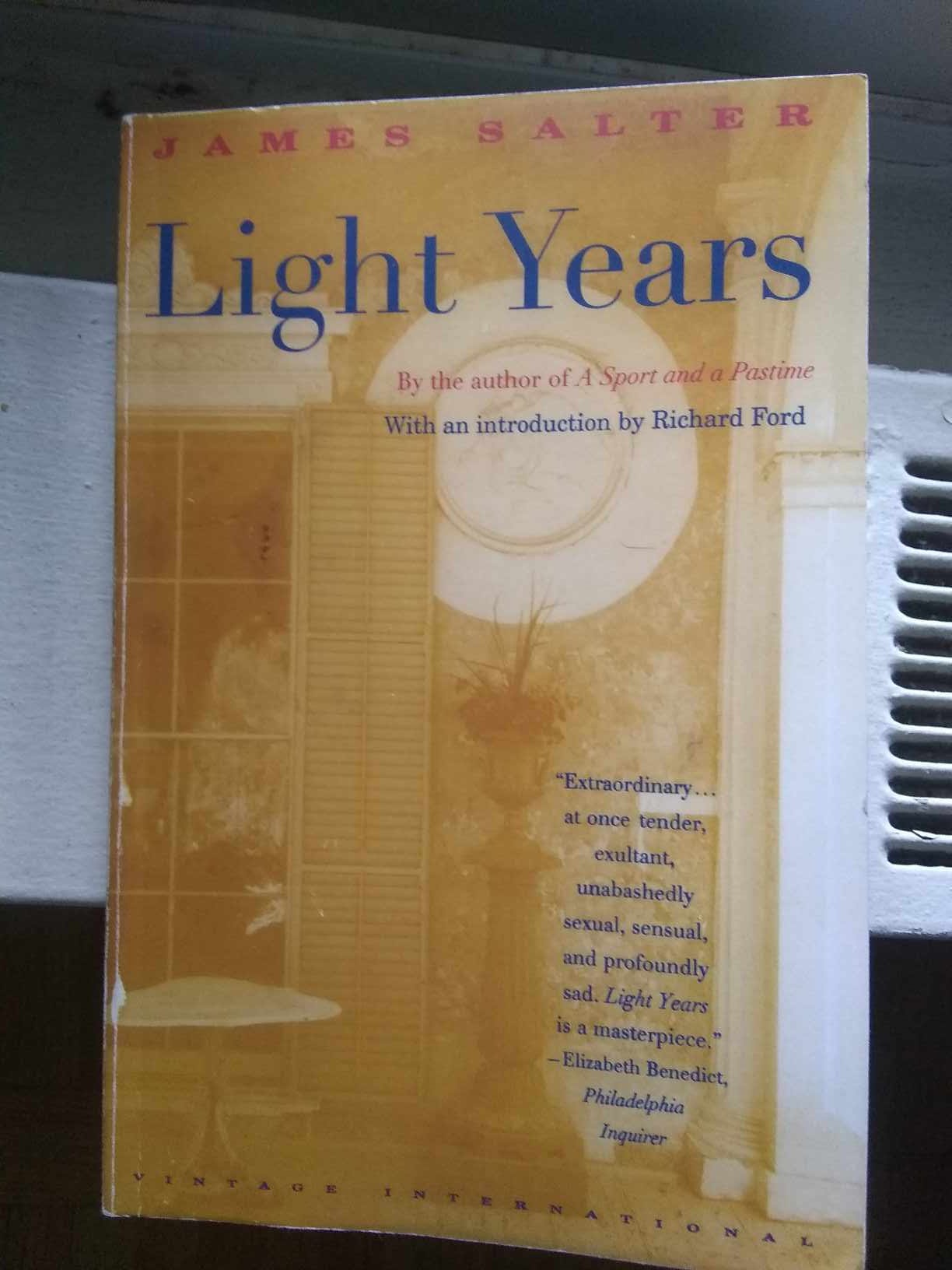

This taking time to process what you wish and what you believe is a good life you’re meant to live is how you could sum up another classic of the 1970s “adultery novel”, a short-hand that doesn’t do it justice I know, James Salter’s 1975 Light Years. (John Updike is a prominent practitioner, but I prefer Margaret Drabble, in whose early novels the young women decide their lives are not finished if a married man ends up preferring to stay with his wife - or if they end up having to raise a child on their own. Her looking back novels, like The Pure Gold Baby (2013), are again like Hadley’s Free Love, dialectic, capable of holding two contradictory developments, coming to moderately optimistic conclusions rather than seeing the era as the root of all evil.)

Light Years left me strangely uninvolved, as it observes the life of a married suburban couple outside NYC as an anthropologist from another culture. It has this habit, sometimes to beautiful effect, of taking a cinematic, taxonomic POV: house, yard, trees, pony, abandoned toys, wind, zooming out to the larger area, or right inside the house, instead of going inside people’s heads parsing impulses and motivation. The narration is also attuned to the passage of time - seasons, children growing up, another festive December with friends coming over for dinner - and jump-cuts without any warning between conversations and scenes. The husband, Viri, is the one who has the first affair, but gets his heart broken and defaults back to marriage, and the restlessness and exploration moves on to the wife of the story, Nedra, who is a stay-at-home, rife-for-Betty-Friedan character. It is a novel that is fairly sympathetic (though I’m not sure it has any feelings either way) to its female principal, something of a stand-in for the critical mass of women who found that getting married, raising children and acquiring life’s purpose that way would not do any more. Not a lot of paths that she takes lead to anything permanent, but impermanence and trying things out is what she is after after decades of living in pre-set modes.

Salter tries to take a life-long view on characters’ affairs - he follows one character until their death and lets another one look back on it all longue durée, the grownup children, the selling of the old family house, the beginning of the age of funerals. But the novel is not told back, it remains on the plane of a restless present tense. Which brings me to my read of the month.

Few people do the looking back narration better than Julian Barnes, with carefully placed revelations along the way, as the image of the past life gains layers. He did it beautifully in The Sense of an Ending, which I was blissfully lulled into until the bizarre plot solution involving an evil boyfriend-stealing mother. In The Only Story, however, there’s no messing up. It’s a 200+page, beautiful and gentle ache, as an older man reexamines the most important storyline of his life, his first big love, the relationship with a woman twice his age who he fell in love with the first summer back home from college at the age of 19. The exuberant and comedic stuff is all reserved for the first half, as was the youthful self-assurance and the absolute conviction of self-transparency and righteousness. Love, the greatest force, will find the way, he is certain. The arc of life is long, he might say, but it bends towards love.

If the first part is the song of innocence, the second obvi is the song of experience. The lovers escape, Susan does manage to leave her violent husband, but she does not have it in her to testify against him in court and pursue divorce. She is also, and the narrator is blind to this, in her life with the young man, equally unresolved, equally in search of purpose, equally… trapped to her old ways. The issue of her drinking is introduced through a third character and comes as a shock (it is not unusual, we are told, for partners and former partners of alcoholics to end up acquiring the problem themselves as if by symbiosis).

The side characters are all exquisite, especially Susan’s old friend Joan, whose one catastrophic love story we also learn. There is one key love story that marks us the most, is the leitmotif of the book - and it didn’t even have to be physical, though most often it is. The Only Story tells what this one story was for Paul, who’s had many relationships since his ten years with Susan drew to a close, all under the sign of the Big One, the forever scar. The West has been more promiscuous than that since the 1970s and I know a number of people who would tell you that it’s two, three, five, or more important relationships that marked them. What abundance, what wealth! But I’m betting most of us would probably zero in to one or two, especially the people who grew up before online dating and who come from cultures in which dating – trying people out for size, passing from one to another in a long sequence - is not a thing.

There’s something else coming into play here as you read, I think - the fact of Julian Barnes’ marriage to literary agent Pat Kavanagh (d. 2008). His was, unfortunately, a famous marriage for a few wrong reasons, one of which was Jeanette Winterson’s fairly public affair with Pat. (In an interview with Decca Aitkenhead for the Sunday Times a couple of weeks ago, Andrew Wylie says that Martin Amis, who dropped Pat as an agent in favour of Wylie, which caused a scandal at the time, told him that Pat had had an affair both with him and his father Kingsley, presumably during different periods in their lives. Was this necessary? I guess he wanted to set the record straight regarding his poaching of Amis Jr. Wylie also claims that he let Pat keep his 10 percent after he worked out a much bigger advance for Martin. No idea what’s the truth there.) Long story short, Barnes has defended uxoriousness as a virtue in various shapes and forms in his writing; I also remember an LRB essay on Georges Braque in which he manages to mention that, unlike Picasso, Braque, the more serious and less famous of the two modernists, was true to his one and only partner for life.

In The Only Story, Barnes created a character who leaves an unhappy, even violent marriage, to eventually catastrophic results. There were moments in the novel where I thought the details of Susan’s falling apart are just a liiiiiiiittle bit sadistic. Really? She finally does what she wants and then - it appears to be awful for her? Leave your spouse, gain an addiction and alcoholic dementia? As in Julia May Jonas’ Vladimir (2022), the strayers outside the wedlock get a cruel and unusual punishment by the end of the story. There’s this conservative undercurrent to both novels, this very un-1970s key.

But TOS has so much going on that in the end this doesn’t undermine it. How oblivious does the narrator remain, how much can we trust him? With the gain of years and wisdom, the story of him and Susan changes before our eyes. And the cell-level changes of how he went from love and being certain what love is, to a realization that he “could not save her”, to indifference - they’re all under Barnes’ magnifying glass.

“That’s one of the things about life,” Susan tells the young man after their first visit with Joan, who lives alone with dogs and starts on the gin too early in the day. “We’re all just looking for a place of safety. And if you don’t find one, then you have to learn how to pass the time”.

“I don’t think this will ever be my problem,” thinks the narrator to himself. “Life is just too full and always will be.”