I’ll immediately admit that this edition of LP is not about Marian Engel’s most famous novel and that this hed is pure click-bait. (If you’re really into Bear, have a listen to this recent episode of one of my favourite book podcasts, Across the Pond, in which the two hosts analyze the book on the occasion of its first UK release.) But Engel will appear eventually, if you read on.

No, the topic of this LP is Working While Writer. (Or an artist, or a composer. I won’t pretend I know if it’s entirely like this if you’re a visual artist, or a composer, but there’s a lot of overlap.)

One of the most referenced things that the New York magazine’s visual arts critic Jerry Saltz wrote in the course of his long career is How to be an artist. Tucked away among the less discussed of the 33 items on his list is an entry which says: find a 3-day-a-week job that would free you from rent, food and bills-related stress and actually let you dedicate the remaining 4 days of the week to what you’re mad keen to do/make/say.

Coincidentally, the 18-21hr a week job is something that I had settled in by then – and it’s been like that ever since I quit my last full-time job to write my first novel, which happened end of 2009. I’ve since had many different 15-20 hr jobs in addition to writing.

The big unspoken in publishing, freelance journalism and the arts is the family money. People who have parents, family members or a partner that will cover them while they’re working in the fluctuating and insecure industry that moreover requires constant training and professional development, or worse in an industry that’s in a free-fall/major reset, will be the ones who last. There’s been a considerable return in many countries in the last three decades towards the figli di papa demographic in arts and literature: only those who already have a solid financial and other support can survive, after accruing student debt of an arts and humanities education, through the wringer of unpaid internships in extremely expensive cities, writing for next to nothing to build a portfolio, plummeting freelance fees and the always late payments, residences, travel, contract teaching jobs that only pay teaching and not the hours of prep or marking, not to mention auditioning, coaching and wardrobe costs for those in the performing arts sector.

But those of us, and I think we are a minority now, who don’t come with a backup infrastructure will always have to be working alongside writing. So it’s a matter of how to organize ourselves so we can thrive and not feel engulfed by what is effectively a 7-days-a-week ON mode.

Now, writers are possibly in a unique position in that their work will in many cases benefit from their accruing life experiences outside of writing or the academe. Professionalized writer who lives off book advances, has an agent, and a network of contacts in the better-paying magazines who will continuously give them work: that’s a relatively recent invention, and while an endangered species in the UK and US, future unknown, in Canada it’s already a rare bird. (Publishing industry in other countries is not as beholden to the agent-&-the-Big-Multinationals publishing system; writers who have agents in France, for ex, are more rare, slush piles are not called that but “submissions”, etc. Publishing in Eastern European countries is even further from the Anglosphere model.) For the most of human history writers have worked on stuff other than writing. Usually the figures like Chekhov (MD), TS Eliot (banker), Kafka (insurance industry) are wheeled out at this point in the conversation, but actually it’s been every writer ever, until maybe the 1980s in the US and the UK. Every writer ever had had to either have a stable non-writerly source of income in the shape of a job, or a family backup system (father’s vicarage, well-off branches of family taking in spinster aunts who scribble, a wealthy spouse).

A lot of writers today teach… writing. Some at prestigious places that pay well – others, with fewer connections, attempt the continuing education departments at universities and colleges, and still others, with no connections whatsoever (this would probably be my lane) will propose courses to school boards’ Learn For Life programs. These kinds of programs can be a great source of joy in a writer’s life, as can the expensive MFA courses be a source of utter misery. There is no guessing what will be more fulfilling. I’ve recently had a chat with an employment counsellor at an Ontario-funded agency and she told me that there’s a massive interest in writing and acquisition of writing skills from all kinds of demographics. Aging boomers are eager to write down their memories before the serious forgetting starts, immigrants are eager to write down their family history. Ghostwriting, memoir mentorship, editing, proofing, there is a lot of demand for this, she tells me. And this anecdotally checks out against my experience. Everybody is writing, there is so much writing everywhere. But the writers’ incomes continue to be on a free fall. What was it, a few thousand dollars average writer income in US and Canada, according to writers’ unions?

Teaching writing is probably more lucrative than writing itself; Leigh Stein is right, the whole system is becoming something of a multi-level marketing scheme.

A lot of us, though, don’t even attempt the teach-writing tack, so we work elsewhere. Some of us go for straight up blue collar jobs. Novelist and short story writer Bill Richardson, a long-time CBC Radio personality, has been writing on Twitter about working retail and also produced a Sunday Edition segment some years ago on becoming a part-time dish washer. Stéphane Larue’s novel The Dishwasher, which won the Amazon.ca First Novel Award in 2020, draws on his personal experience of working in a restaurant. I’ve been applying with gardening and landscaping companies for landscaper jobs, but as I have zero experience, no luck so far. It appears that more than four decades of sitting (while reading and writing) has made my neck and back very unhappy, and now in my dotage they are rebelling. So I’m looking for something more manual, that’ll get me physically engaged. I’d be content hauling bags of soil, planting stuff, dragging hoses across lawns, raking leaves. I almost convinced a bricklayer to take me as an apprentice last year. I’ve looked at the Second Career funding, but writers with degrees wouldn’t qualify for a program designed for the laid off workers in manufacturing. Would be nice to be a carpenter, or electrician when not writing, no? Welder by day, dancer by night, as the movie Flashdance (and Marx, dreaming of a communist utopia) would have it.

Until then, I’ll press on with the side business of being a 18-hr-a-week administrator. I would not recommend admin jobs tout court. A lot of them are paid only slightly above minimum wage. Almost none of them, if part time, come with any kind of benefits. But pt admin jobs in the property management of co-op buildings tend to be different: usually paid over $21 an hour, with benefits, paid vacation and sick days. (For international readers: co-operative housing in Canada means rent stabilized living, often in heritage mid-rises, where you’re supposed to volunteer some of your free time toward building operation or things like checking up on seniors etc. More than eighty percent co-op members however opt out of that altogether once they move in; there’s usually about ten to twenty percent of people who are active in gardening committees, volunteer for boards etc.) Admin jobs in government of course are the best deal, but hard to come by.

You could of course work in a bookstore as many writers do, but bookstores pay little, and you’ll have to wear a mask for a long while yet in retail in Ontario. I know a number of writers who work in publishing, which is just dreary: having to work on other people’s writing instead of your own. There are many editors among writers that I know, and I can’t say I envy them. They are paid much better than I am, but I’d recommend getting away from your sector as much as possible in your parallel job, for all kinds of reasons.

So things I’ve learned over the many years of admin jobs in Canadian cities:

- hours are all made up and have nothing to do with actual work done or real productivity. If you’re remotely productive in these office positions, you’ll finish a lot in the initial flurry of work and then stare at an empty hour or two, or worse. The 7 or 8-hour workday is a sort of impressment: your body must spend that time at the desk even though the work’s been finished. The left could gain a lot of supporters if they start talking about reorganizing the workday and the existing division of labour. Could the office jobs be redefined to combine the best of the consultancy positions (you work until the work is done and then you’re gone) and permanent employment (benefits, vacation)? Nobody’s talking about this. The 4-day-a-week thing resurfaces here and there in the media, so I guess that’s a start.

- Productivity is rewarded not with free time, but with more work

- There’s a huge component of emotional labour in administrative and service industry positions, which are anyway most often occupied by women. Humouring, deescalating, anticipating needs: all that is now part of the job. And where do I even start on the question of gender when it comes to management styles. I’ve had a lot of female bosses who expected me to provide compassion and care as part of a purely admin job: nothing less than an asymmetrical friendship. If you work for a woman, every administrative job is a personal assistant job, looks like it. Male managers can be a pain in a different way; taciturn, dislike having to justify their decisions, very no frills in communication. There was a manager of a maintenance company in my last job that would take out his phone and start checking messages in the middle of a two-person meeting that he had called. He just decided it was too much of an effort, this exclusive attention during a meeting.

Still, these are fairly easy jobs, especially if the writing side of life is stressful or too eventful, to come back to as a safe (and often mindless) harbour. You’ll be making very few decisions yourself. That’s exactly the kind of backup job that you need if, say, you’re writing about something that might get you cancelled. It’s easier to find integrity if your entire livelihood does not depend on what you write and what opinions you express. That way you can write and express opinions fearlessly.

One downside of a part-time job is that you may not notice how unhappy you are in it for a long time, because it’s not top of mind, it’s a side hustle. This is what happened with my last job, which I just left after more than 7 years. When a p-t job is a drag, you tend to notice it less than you would a f-t job. As someone who grew up in a communist country, the constant changing of jobs is something I had to learn. The way commodities are improved in capitalism, so it is with humans: there is this constant urge for optimization. It’s unusual to stay at a job for a decade, isn’t it? And staying in the same job for 20 years hints at a lack of ambition. So even if it’s a part-time job, there could always be a more suitable one. I’m now in a roster of a large temp agency that sends admin jobs to your inbox, which has an in with the provincial government. There’s a lot of crazy stuff (a market research position that pays $17 an hour!) but some decent ads too.

It’s important to have skills that can travel with you, should you leave the country and become an expat (again); so I got my TEFL license with an international program during the pandemic. I’ve been volunteering in adult literacy with Frontier College last couple of months, and that’s been kinda fun. I am still dreaming of a more physical job that would get me off the chair, so that’s not entirely gone from the radar either. What’s the name of that writer who lives up north and raises huskies for dog sleds for her non-writing job, I forgot? She often writes about that side of her life in her journalism and on social media.

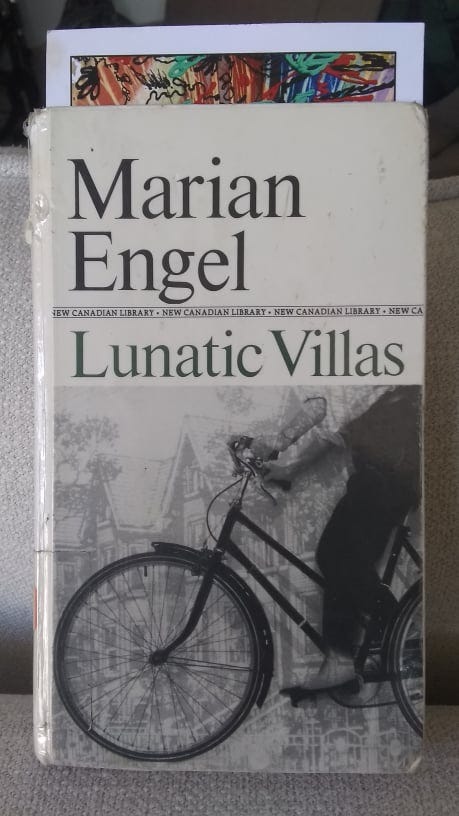

But meanwhile, my new co-op job, 18-hrs a week plus the frills, is in the part of Toronto where Marian Engel lived. There’s a park named after her, and her last novel, Lunatic Villas, is set in that neighbourhood. A fan site says she used to live on Marchmount Road, just north of the current Marian Engel park. I found the book and started reading, and it’s immediately most delightfully a comic novel, that exotic bird in the CanLit of today. “Lunatic Villas”, informs the book blurb, “is a chronicle of one year in the life of Harriet Ross; struggling freelance writer, keeper of a brood of seven fiendish children, and focus of the bizarre comings and goings on “Ratsbone Place”, Toronto’s trendiest street of converted townhouses…”

Ooh: I love Lunatic Villas! I also finally got around to reading Bear a few years ago, and have thoughts about it that don't seem to align with those of her critics or fans. It's not my favourite, however. Engel, oddly enough, manages to write credibly about women's ordinary lives while working pretty exclusively in art-related fields, often as a volunteer.