When did manufacturing flee Toronto en masse? After the NAFTA was signed, after China joined the WTO? When multinationals ate up small and medium size retail? When sitting on a chunk of real estate became way more profitable than making things?

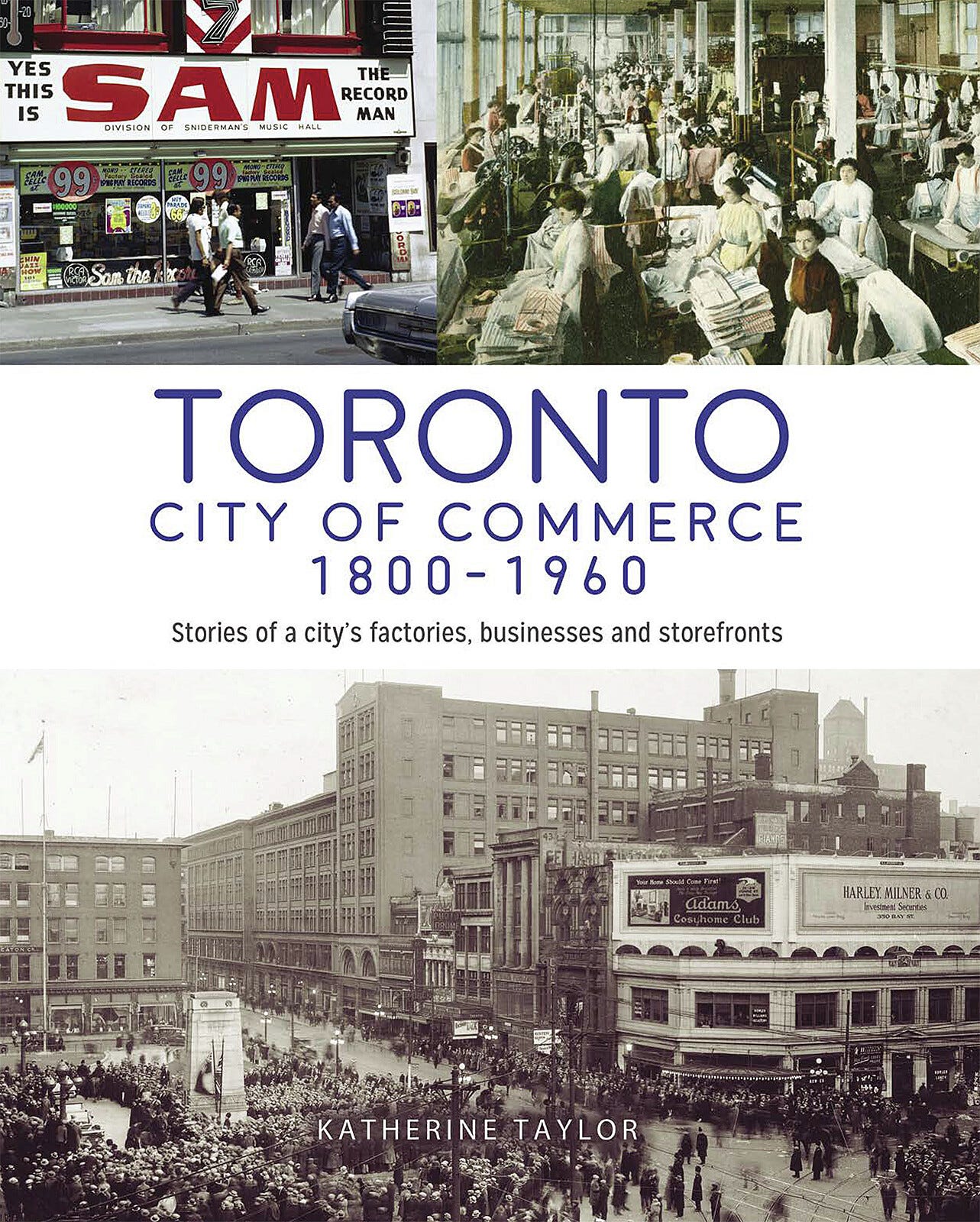

Katherine Taylor’s “One Gal’s Toronto” is a thoroughly and lovingly researched WordPress blog about Toronto’s history. This year Taylor published her first book, the richly illustrated Toronto, City of Commerce 1800 – 1960 which, while beautiful to leaf through, is a melancholy to read. Most of the businesses she features are long gone, and worse, the technologies that they made money on are long gone as well, blanked out from the memory. Who among you will know what a cyclorama was? This kind of display of the series of paintings within a vast circular building was all the rage in 1880s, just before the moving pictures made their entry. (Toronto’s cyclorama building on York and Front was torn down in 1970s, clearing the way for Citigroup Place.) Or, who knew through what steps the ‘peep show’ became what it means today? It originated in these gathering places called penny arcades where you could pay to have yourself weighed, have your fortune told, play coin-operated games, or peep into machines to watch amusing images, which, such is the march of commercial entertainment, became risqué pretty fast. When the moving pictures became mainstream entertainment, you would go to a vaudeville theatre to watch – places like the Elgin and Winter Garden which were shut down by the 1980s and left for dead until the Ontario Heritage Foundation had a different idea.

City of Commerce looks at this muddy backwater of a town called, unambitiously, York from its unglamorous beginnings till just about far enough from the end of the WWII as the age of consumerism was beginning in earnest – and the age of youth culture, the prosperous sixties and multicultural immigration. It’s a book about the entrepreneurs and businesses that marked this period, told in brief chapters that include at least one B&W picture of the company in its era, and a picture taken by Taylor herself of the company’s phantom sign that survives to this day. Some of the big business is inevitably American (Woolworths, Wrigley’s, Coca Cola, Loew’s Theatre), but most are Canadian, ranging from small to moderately large. (It’s the pre-corporation age after all.)

Metalworks are represented by James Good’s Foundry (f. 1844), which produced “ploughs, stoves, potash kettles and threshing machines” and also the first locomotive ever in Upper Canada, and there’s the Ideal Aluminum (1922) which started big across Canada but disappeared within 10 years. Companies that manufactured and sold appliances or industrial equipment are well represented: Richard Bigley (1875), Canadian General Electric (1895), Thomas Davidson Manufacturing Co. (1912), Coleman (1920), and Beatty Electric Washers (1923). In lithographing, printing and publishing, there’s the 1849 Rolph-Clark-Stone (phantom sign can be found in the Carlaw-Dundas E area), the 1913 Beare’s (phantom sign on Wolseley near Queen and Bathurst), Reliance Engravers (1917), and Acme Carbon and Ribbon (1934).

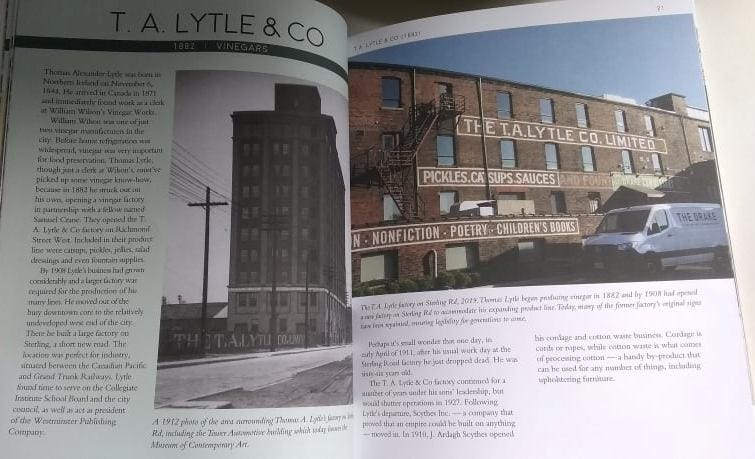

The big bunker of a building at the foot of Bathurst that used to be the home of Canada Malting Co. Ltd. (1928) is a designated heritage site now, its future use unclear. It’s just there, looking monumental, getting more and more decrepit. The building that housed The T. A. Lytle & Co’s Vinegar and Pickles factory (1882) has had more luck: it’s the home of House of Anansi and its bookstore, and the Drake Commissary restaurant, plus I presume various other offices in its top floors. The tallest building in that entire post-industrial area is the Tower Automotive building which now houses the MOCA.

Tip Top Tailors (1909), whose sign survives on the old building, now lofts, on Fleet near Lakeshore Blvd, and William H. Leishman’s (1914) and Gelber Bros (1920), original building still on Richmond and Duncan, are the clothing industry reps in the book. Also featured in manufacturing, a company that made glasses (Imperial Optical, 1906, sign on 21 Dundas Square), and Charles Sewell, Watchmaker (1836). Standing for Canadian indie (heh) car industry there’s Russell Car Company (1904), which later merged with the now vintage label, the CCM or Canada Cycle and Motor Company.

Taylor reserved a large section of the book for retail, and while endogenous retail’s doing comparatively better than manufacturing small or large, it’s become hugely concentrated, so the book is a useful reminder that it wasn’t always like that. Recently the pot shops have changed the entire formerly lively stretches of Toronto and have made the previous expansion of Starbucks and the fast food chains look positively restrained in comparison. Independent pharmacies like Waltman’s (1948, sign survives on the original building on 1147 Dundas W), milliners like Parkdale Millinery (1917, located on 1412 Queen W), furniture companies like F. C. Burroughes (1887, from 1907 located on Queen and Bathurst, the painted sign survives) are few and far between. While the independent hardware stores and designer-owned clothes shops still exist here and there (see Dudley’s on Church, and Studio Fresh on Danforth), massive corporations like SDM, Canadian Tire, Walmart, Ikea-Leon’s-Wayfair-whatever -- not to mention Amazon -- have absorbed all our shopping. As they tend to be vast establishments, they are usually to be found in malls or outside urban centres, contributing nothing to the streetscape. But even that is better than the blank anonymous stare of the marijuana store that’s becoming ubiquitous.

Taylor doesn’t go into any of this, not directly. She is not making the argument that many many small business vs. 3 or 4 large ones are better for democracy and definitely better for city life – but I am. I’ve read recently an interesting work of political theory by Elizabeth Anderson, Private Government: How Employers Rule Our Lives (and Why We Don’t Talk about it), in which she dedicates the first half to the history of the idea of being one’s own boss and a genuinely free, monopoly- or duopoly-free market which I’m not sure we’ve ever experienced? She recovers Adam Smith, the Levellers, the Chartists, Thomas Paine and Lincoln as the early workers/independent business owner’s rights activists:

“Preindustrial labor radicals, viewing the vast degradation of autonomy, esteem, and standing entailed by the new productive order in comparison with artisan status, called it wage slavery. Liberals called it free labor. The difference in perspective lay at the very point Marx highlighted. If one looks only at the conditions of entry into the labor contract and exit out of it, workers appear to meet their employers on terms of freedom and equality. That was what the liberal view stressed. But if one looks at the actual conditions experienced in the workers’ fulfilling the contract, the workers stand in a relation of profound subordination to their employer. That was what the labor radicals stressed.” Both Marx and Smith, says Anderson, “marveled at the ways market society drove innovation, productive efficiency, and economic growth. Yet both deplored the deskilling and stupefying effects of an increasingly fine-grained division of labor on workers” (p. 35).

I am aware that when I bemoan the flight of manufacturing from Toronto, that there is some romanticizing of the manufacturing era happening there. But making stuff with your hands is I think important for one’s well being – and there’s a good philosophical case for it, for ex in Matthew Crawford’s The Case for Working with Your Hands or Why Office Work Is Bad for Us and Fixing Things Feels Good (Viking, 2011). Making stuff locally, as the last year’s pandemic supply and transport problems illustrate, is equally important. We tend to forget this when the trading chain is well oiled. What do we still manufacture in Toronto on a large scale? There is the Cadbury plant on Gladstone Avenue, the Red Path sugar refinery on Lakeshore E, the meat-processing hub north of the Junction. There’s a ton microbreweries around town, and at least one family-run gin distillery near Eastern Avenue and Logan. There are software companies that do well then get sold to a multinational. I use Wave App for invoicing, for ex; it used to be a Canadian business, located in the old industrial hub on Carlaw-Dundas E, but it’s part of an American company now. FreshBooks is still I think a Toronto company – located in another post-industrial-turned-fancy-office-building in the Junction Triangle. Kobo, once Canadian, now Japanese, has a post-industrial building in the Liberty Village. (There’s a recurring theme here…) Another post-industrial building that had been redeveloped, the 401 Richmond, is thankfully not carved into lofts but made into a small-business hub with somewhat stabilized rents.

A lot of the formerly industrial establishments in Toronto are now either lofts, or tech offices, or high end service industry offices. Google, Microsoft, TikTok, Amazon, Netflix, Reddit, Uber all have offices in Toronto and many choose the old downtown buildings with the gritty industrial pedigree. But the making of clothes, shoes, toys, furniture, household items, bicycles, and hey, medical equipment, masks and pharmaceuticals, to name just a handful of things that immediately come to mind, happens in foreign countries, and the production of stuff that we do make locally (books!) depends on international supply chains of raw materials and of course petrol.

Food industry is a somewhat different story, but the conglomerates predominate there as well, even though they are Canadian conglomerates. Every few days I read a piece where someone is calling the Canadian dairy industry a cartel; the small cheese and egg producers would probably have a lot to say on this topic. The term Big Ag was coined for the US situation but would be perfectly adequate for us too I expect; as would be the concept of chickenization, originally from Christopher Leonard’s Meat Racket: Secret Takeover of America’s Food Business (2015), popularized by Zephyr Teachout and her activism and the book Break ‘Em Up: Recovering Our Freedom from Big Ag, Big Tech, and Big Money (2020).

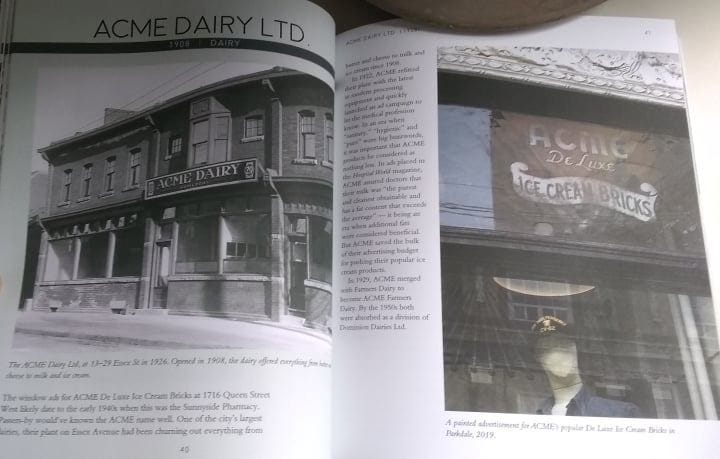

Taylor features only one dairy producer in her book, the ACME Dairy Ltd. and their De Luxe Ice Cream Bricks store, the sign for which still lingers above a Parkdale storefront. Back then one of the city’s largest diaries, ACME would today be positively modest — an indie milk brewery, practically.

There were probably many I could think about if I took the time, but I certainly hope she included Borden's milk on Spadina crescent just north of college St. The big old building on the east side of the street is still there I believe. After visiting the boys and girls house at the main library at St. George we would walk to Borden's and get an ice cream treat.